|

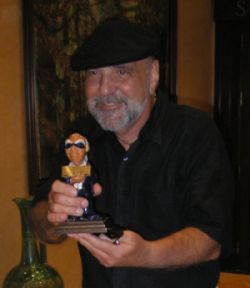

To talk about Basil Poledoris is to talk about film music at the highest degree. His huge talent has generated so many masterpieces that he should be justly considered as a Legend. According to this, here you have possibly the most important interview ever published by BSOSpirit.com. To talk about Basil Poledoris is to talk about film music at the highest degree. His huge talent has generated so many masterpieces that he should be justly considered as a Legend. According to this, here you have possibly the most important interview ever published by BSOSpirit.com.

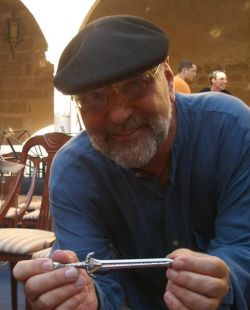

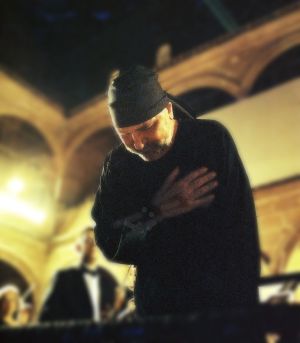

Poledouris spoke to us a few months before we met at Úbeda, and here he opens his heart in an emotive interview, a journey through his career and an extraordinary complement to his attendance to the past International Film Music Conference 'Ciudad de Úbeda'. All of us who had the privilege of meeting him then, touched the sky just for a few days. Not only Basil is one of our idols, he is also a very beautiful person, a model for all of us regarding how to live and how to attend people. Thank you very much, Pole, now we admire you more than ever.

BSOSpirit (BS): First of all, we would like you to know that you are one of the most beloved

composers for the BSOSpirit team. Indeed we all feel this is the most important

interview we’ve done up to now given that, in our view, you do rank among the 10

most influential and talented film music composers in history. Basil Poledouris (BP): Thank you. I appreciate your feeling that way. I assume that means that these

answers had better be good then.

BS: Could you tell us something about your first steps in the film music world?

How did you get interested in writing scores and making a living out of it?

BP: I began studying piano at the age of seven years and pursued the goal of

becoming a Concert Pianist Cheap Zithromax. I entered the School Of Music at The University Of

Southern California, studied Piano and became interested in Conducting especially

Opera. I think that the drama and spectacle of Opera appealed to me

and upon turning 20 years old took that one step further in the direction of the

Dramatic Arts by quitting Music entirely and entering the School Of Cinema. To

put this in proper perspective one must realize the social, political, and artistic

mindset that prevailed in the mid-1960’s. The United States as well as many

Nations of the world were undergoing rapid, severe, and, sometimes, violent

change.

The Vietnam War polarized people in America and became a framework

against which all else was judged. It was a very unpopular war (what wars aren’t)

and coupled with the Civil Rights Movement in the United States people were

galvanized politically, socially and culturally. Buy Zithromax Online - Most young persons at that time saw

through the hypocrisy and Political Machinations of the government and banded

together through many causes with the Hippy Movement being one of the main

support lifestyles that many felt comfortable with as it was socially liberal and

committed to forcing dialogue and bringing about options for change in the

somewhat limited possibilities that were accepted in mainstream thinking at that

time.

BS: In spite of the fact of having written a score for John Millius’ 1966 short film ‘The Reversal of Richard Sun’, it’s quite remarkable to realise that you first

pursued an acting career in pictures like ‘First to Fight’ before becoming a film

music composer. It was this picture that you first met your wife Bobbie, is that

right? BS: In spite of the fact of having written a score for John Millius’ 1966 short film ‘The Reversal of Richard Sun’, it’s quite remarkable to realise that you first

pursued an acting career in pictures like ‘First to Fight’ before becoming a film

music composer. It was this picture that you first met your wife Bobbie, is that

right?

BP: This question has many incorrect assumptions in it. For starters, The

Reversal Of Richard Sun was written and directed by William Phelps III. Milius

played a leading acting role in the film and was probably the ‘violence advisor” and

showed everyone how to load and fire guns containing blank ammunition that

were used in the filming.

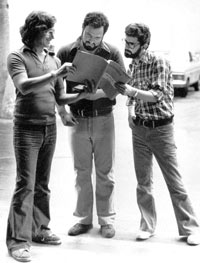

Most students in the Cinema Department helped out

other students with their projects. Caleb Deschanel, Walter Much, George Lucas,

Randal Kleiser and I were in minor roles.

Randal Kleiser, Taylor Hackford, and I made money by acting in Hollywood

films and often just being part of the background action in scenes. I never

considered myself an actor and certainly never pursued a career in this field

although as an aspiring Film Director it was an extraordinary opportunity to

observe, learn and participate in the art to which we were devoted.

First To Fight

was just one of the many jobs taken in that spirit. My ex-wife, Bobbie, was also a

student at the University and we met at a social exchange between my fraternity and her sorority. She was getting her degree in both Psychology and Drama and

as her father was a well-known British stage and film director (Peter Godfrey) we

naturally shared an interest in film, drama and music. At that time, however, she

was unaware that I was a musician. BS: How crucial would you say Bobbie has been for your career as a musician?

BP: Without the support, encouragement, belief in and willingness to sacrifice

herself for my art, I never would have had the courage to become a film

composer. How crucial is that? Enormously. Having interest and love for some

one else’s career and helping to guide the many many choices to be made along

the way, exhibits an extraordinary and unique selflessness, which is rare.

BS: You’ve often stated that you feel rather closer to European composers like

Prokofiev than to some of the American ones who clearly have had a big influence

on some of your colleagues. Could you tell us what lessons have you learned from

those European musicians?

BP: Let us take Nino Rota as an example. Rather than scoring a picture frame by

frame (which I have done many times), if we hear the Godfather theme, there is

instant recall of any scene from the film. What he has done has captured the

essence of the dramatic and psychology content and intent of the writing. The

same holds for all of Sergio Leone’s brilliant films by Ennio Morricone, and of course, Alexander

Nevsky by the great Prokofiev.

BS: You have collaborated with John Milius on many projects. Is there a particular

picture among them that you think was more decisive in terms of helping you to

grow up as a composer? BS: You have collaborated with John Milius on many projects. Is there a particular

picture among them that you think was more decisive in terms of helping you to

grow up as a composer?

BP: All of John’s films have unique opportunities and challenges as a composer.

They also have the absolutely dedicated support of a director who has very strong

feelings about the role that music plays in realizing his vision. He is insistent that

the music speak directly, clearly and represents the subtext of the entire film. His

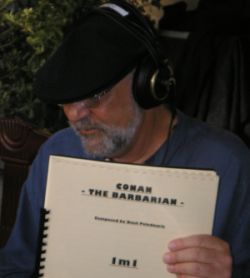

requirement that Conan should be an Opera referred to the size and scope and

storytelling requirements of the music and to a much lesser extent, the lyrics.

He

also wanted it to sound mythological as if it had been passed down through the

ages, As a Ritual that has been waiting 10,000 years to happen. He felt that if

the music could capture these qualities, that the audience might feel as if they

were part of a larger, timeless whole. As the Prologue of Conan states, that

which does not kill us makes us stronger. I feel that way about all of John’s Films. BS: Did you ever find out why John decided to choose Jerry Goldsmith for ‘The

Wind and the Lion’?

BP: There was nothing to find out as it was well known. Simply put, at that time

John didn’t have enough power to have an unknown composer score a major

motion picture. Jerry was an excellent choice and I think it is one of his finest

scores ever. I know that John drove him nuts by insisting on a thematic score but

to my ears, it stands heads and shoulders above many of his other efforts.

BS: From your current standpoint, how do you feel about your contribution to a

film such as 'Red Dawn' which was labelled by some critics as quite a

thematically-controversial picture? BS: From your current standpoint, how do you feel about your contribution to a

film such as 'Red Dawn' which was labelled by some critics as quite a

thematically-controversial picture?

BP: Controversy is good as it should create a dialogue. Red Dawn was a

political fantasy with a lot of heart. I never perceived it as a right-wing paranoid

raving. Look at Hungary, Poland and Chezkoslovakia after WW II as models. I do

wish that the villains in Red Dawn had been the giant multinational corporations

instead of the Cubans and Russians. Easy to say because I didn’t write the script.

BS: ‘Farewell to the King’ is certainly one of the most outstanding scores you’ve ever created for John Milius. In the same vein as with ‘Red Dawn’ was there a point in time where you might have thought the core themes behind the storyline might have been misinterpreted by a critical sector of the audience?

BP: I fail to see the similarities in the themes of these two films. In those days no one paid much attention to the critical sector of the audience if they were interested in creating anything other than sequels or remaking old television shows.

BS: What would you highlight about your work on ‘Farewell to the King’? BS: What would you highlight about your work on ‘Farewell to the King’?

BP: John’s dictate for Farewell was that the main theme was played often and in, sometimes, unconventional scenes. He wanted to remind the audience that this was a film about the relationship between the Botanist and the King and requested that the theme contained a sense of warmth and heart. That was unusual for him and I think it was a bold requirement that worked very well. Of course there are a few action scenes where playing this type of music was inappropriate and I scored it

more in an action genre.

BS: In 1982 you were in Spain, more precisely in Almería. What was the reason for your trip at that time?

BP: To witness some of the filming of Conan The Barbarian.

BS: Have you ever since come back to our country?

BP: Unfortunately, no. I have thought about often, but never got the opportunity to return.

BS: What do you expect to find in Úbeda this summer?

BP: Good music, good like minded friends, good dialogue, great scenery and terrific Flamenco.

BS: Since we are the organisers of the Conference, it is our duty to underline the fact that there's a whole legion of film music enthusiasts who are quite passionate about your work. Are you aware of the tremendous role you play for the film music fan community? BS: Since we are the organisers of the Conference, it is our duty to underline the fact that there's a whole legion of film music enthusiasts who are quite passionate about your work. Are you aware of the tremendous role you play for the film music fan community?

BP: Not really, but it is good to be told this.

BS: Needless to say that you are going to be the most influential speaker this year, let alone given the fact that you will be conducting your own works live in front of a large audience. What is that you intend to achieve with this unique event which, for many of your fans, is already seen as a dream come true?

BP: The music will be performed to the film. It is very sparse with dialogue and looks beautiful. With an orchestra and choir performing selections of the score live, it should be very exciting. Also, it has been many years since this music was performed live and then only on a recording stage, not in a live concert setting. To give it voice again has always been a dream of mine.

BS: Is there any hidden surprise you have in mind for the Conference or perhaps in the light of the concert?

BP: The main surprise will be whether or not I actually have the energy to conduct 40 minutes of Conan live. It’s going to be a lot like Survivor. Maybe we should set up a betting or gambling concern with odds posted after every cue against making it to the end?

BS: We are very much certain that Conan will be the one score that you will be most often asked about during your stay in Úbeda. Now we wonder if this is still a particular meaningful score for you also given the significance it has had in your career or rather if, as it happens to be the case with many authors, you are somewhat tired of all the hype surrounding the former? BS: We are very much certain that Conan will be the one score that you will be most often asked about during your stay in Úbeda. Now we wonder if this is still a particular meaningful score for you also given the significance it has had in your career or rather if, as it happens to be the case with many authors, you are somewhat tired of all the hype surrounding the former?

BP: I haven’t thought about Conan for the past twenty or so years and it is refreshing to take a long look at it after so many years. Some of it is actually pretty good!

BS: Should you happen to choose one or two particular themes of this score, which ones would they be?

BP: The Orgy and The Funeral Pyre.

BS: One of the most remarkable qualities of your music for this film, and one that seems to make it truly unique, lies in the fact that instead of creating a theme for each character you rather opted for writing a leitmotiv for each place, situation or adventure foreseen in the plot. This way you ended up developing a non-repetitive score, full of textures; something quite uncommon to other soundtracks. Did you envisage such approach by your own from the outset or was this rather something that took shape with the help of John Milius as the two of you got more and more involved in the project?

BP: John has uncanny instincts for the way music becomes an integral and non repetitive part of his films. Conan, he told me, should sound like an opera with the music telling the story much as story line of the film does. The film starts at on the Steppes of Russia and gradually proceeds toward the Mediterranean Sea. BP: John has uncanny instincts for the way music becomes an integral and non repetitive part of his films. Conan, he told me, should sound like an opera with the music telling the story much as story line of the film does. The film starts at on the Steppes of Russia and gradually proceeds toward the Mediterranean Sea.

The Harmonies trace this journey by being rather pagan and cruel but warming up by the time we get to the Cue Theology and Civilization after the transition cue of The Atlantean Sword. Then it becomes even more harmonically rich with The Orgy culminating in The Funeral Pyre which then takes us back to revenge mode until the death of Thulsa Doom. I was speaking with John last week and he mentioned that he would never be allowed to take the screen time today that he did when Conan is sitting on the steps of the Mountain Of Power while contemplating his next move before burning down the evil den and offering his compassion to the Princess whom he is obviously going to return to King Osrik (even though he has been murdered unbeknownst). The Harmonies trace this journey by being rather pagan and cruel but warming up by the time we get to the Cue Theology and Civilization after the transition cue of The Atlantean Sword. Then it becomes even more harmonically rich with The Orgy culminating in The Funeral Pyre which then takes us back to revenge mode until the death of Thulsa Doom. I was speaking with John last week and he mentioned that he would never be allowed to take the screen time today that he did when Conan is sitting on the steps of the Mountain Of Power while contemplating his next move before burning down the evil den and offering his compassion to the Princess whom he is obviously going to return to King Osrik (even though he has been murdered unbeknownst).

I assume this is how he became King? It is truly an extraordinary moment in the movie and humanizes the Conan brute enormously. The other thing I should mention is that I started work on the film before shooting started and was solely engaged with the writing of Conan for 12 months. An unusual but welcomed amount of time considering the requirement of re-telling the story musically and utilizing the variation and development necessary to prevent the repetition of which you spoke of earlier. I assume this is how he became King? It is truly an extraordinary moment in the movie and humanizes the Conan brute enormously. The other thing I should mention is that I started work on the film before shooting started and was solely engaged with the writing of Conan for 12 months. An unusual but welcomed amount of time considering the requirement of re-telling the story musically and utilizing the variation and development necessary to prevent the repetition of which you spoke of earlier.

BS: 2007 will mark the 25th Anniversary of Conan. A good number of film music enthusiasts, if not all, are longing to finally have this score properly released, i.e. remastered sound, featuring additional cues, a deluxe booklet, accurate liner notes, etc. Do you know if this is likely to happen soon?

BP: As this score is dear to me, I have given much thought to its re-recording. Since the remastering process would be costly, if in fact the 24 track masters could be found, I might be inclined to undertake such a venture.

BS: Are you aware that Robert Townson is coming to Úbeda? I guess quite a few fans will take advantage of the occasion to draw his attention on the question of releasing a complete soundtrack to Conan.

BP: I thought that he had. Soundtrack collectors should realize that there is a difference between a Filmscore and an album. Many cues written for a film don’t necessarily make for a satisfying purely listening experience even though they may have been appropriate for the film itself. Kind of like comparing apples and bowling balls.

BS: Another relevant guest will be Doreen Ringer-Ross, head of BMI Film Music Department, the rights performing organisation you belong to. We have a similar body in Spain, namely the SGAE. What role does BMI play for a US film music composer in your opinion?

BP: Doreen Ringer-Ross is also a friend whom I very proud to be numbered among as close. Her role at BMI would be unthinkable if it were any one else. She is the Liaison between the Film Music Dept. in Los Angeles and her advice, input, encouragement for young, talented artists is rather like an impresario would have been in older days. One savvy lady.

BS: We have heard that John Milius is currently working on a new film called 'Jornada del Muerto', which is likely to be released next year. Did he already approach you for this picture?

BP: Jornada del Muerto is pure Milius, with its action, sense of code, camaraderie and heart. If the film gets made I will score it.

BS: How would you describe your working relationship with Paul Verhoeven? BS: How would you describe your working relationship with Paul Verhoeven?

BP: Paul Verhoeven also has the same kind of intensity about the musical contribution to his films as Milius and am amazed that I survived both Robocop and Starship Troopers. Flesh and Blood was kind of a known entity in that it had a specific geography and time period which is, at least a starting point. Science Fiction requires more demanding solutions and invention. The composer needs to create a musical environment, which supports the Director’s vision of a place and/or psychological situation that we may never have encountered before.

BS: 'Flesh and Blood' was quite a shocking picture at the time. Filming took place in Spain, mainly in Ávila. Didn't you feel like coming back to Spain once again after your previous experience with Conan?

BP: This film was completely shot and edited when I viewed it in Los Angeles so going on location wasn’t an option.

BS: Could you tell us how you tried to echo the depiction of a ruthless and cruel society trough your music? BS: Could you tell us how you tried to echo the depiction of a ruthless and cruel society trough your music?

BP: There are many complex themes dramatically in the film which I attempted to manifest musically. First off, we have the Mercenaries who will fight for any cause. Then we have the priest who understands that he and Martin can manipulate the others through the power of religion merged with politics.

Then there is the swashbuckling, land pirate kind of adventure theme followed by the

Agnes-Martin love theme, then the Agnes-Steven love theme, the final assault, the attempt at killing Agnes followed by the resolution of Martin smiling as Agnes and Steven ride off and he climbs out of the chimney of a burning castle.

Pretty cool stuff for a film composer to chew on. I loved this film and its unabashed ruthlessness which was probably very close to life as it was in those days. Not much romanticizing in this move. It is Verhoeven at his multi-faceted best, showing us many points of view and realities, simultaneously. Paul earned a PhD Degree in mathematics and he thinks three dimensionally, which is always a welcomed challenge to portray musically. BS: One might say that your score to this film seems to show a slight Spanish influence. Why so? Was there a clear intention of having a more Hollywood-type of soundtrack?

BP: Clearly The Hunt For Red October was intended to have a Russian influence as Lonesome Dove, Amerika and Quigley Down Under were drawn from American folk and classical constructions. The Touch was most certainly Chinese in its rhythms, open harmonies and melodic construction, but I have never considered Flesh & Blood as having a Spanish influence. Very interesting! Maybe some of the landscape crept into my awareness at an unconscious level?

BS: Has Paul ever told you why he did choose to work with you on some projects and with Jerry Goldsmith on others?

BP: When Paul asked me to score Total Recall I had already The Hunt For Red October. It nearly killed me but I had to refuse the assignment, as I don’t score two films at once feeling it to be a great disservice to both pictures. His choice of Jerry was perfect and Jerry has provided him with wonderful soundtracks. Paul is loyal but is willing to cast composers like he would any other of his films. He once told me that he utilized Jerry for a more intellectual approach and me for a more emotional approach. It made perfect sense at the time and still does.

BS: One very interesting feature of Robocop was that its main theme does never

show up before we get to see Murphy turning into the actual Robocop character.

There were many fans who, after listening to the soundtrack, thought they would

come across this theme already from the start, in the Main Titles. Why did you

choose to save the theme for later in the movie? BS: One very interesting feature of Robocop was that its main theme does never

show up before we get to see Murphy turning into the actual Robocop character.

There were many fans who, after listening to the soundtrack, thought they would

come across this theme already from the start, in the Main Titles. Why did you

choose to save the theme for later in the movie?

BP: There were two reasons for this. One, the Main Title sequence is 20 seconds long. So, no time to state anything except a premonition of what’s to come- a little mystery a little violence in the force of its presentation and a little taste of what to expect harmonically. The second reason is that we don’t know who this guy is yet-just a cop in the not too distant future who is checking out a routine call perhaps. It is not until Murphy becomes half human and half machine that we discover whom the main character really is. We learn about his past only after he has become Robocop. Neat, huh?

BS: Starship Troopers is one of your strongest, large-scale orchestral scores, full of big action pieces. What was the musical idea pursued by Verhoeven for a picture that sometimes seems to be wary about totalitarian regimes and all of a sudden makes an unexpected turn, finally adopting an approach that could be well understood as in favour of the use of violent means?

BP: This is a cautionary tale of how governments manipulate their populations to hate, to kill shamelessly in the name of whatever god or social philosophy that their masters or elected politicians can utilize. BP: This is a cautionary tale of how governments manipulate their populations to hate, to kill shamelessly in the name of whatever god or social philosophy that their masters or elected politicians can utilize.

How else could you actually make people understand concepts like “collateral damage” or suicide bombers unless governments were inciting the populace into the lunacy of revenge or a Holy War no matter whether it is Crusades or Jihad. There were Gods of War but they are as outmoded as the eight track tape recorder. BS: What was the size of the orchestra you used?

BP: Probably 100 or so musicians, including Pipe Organ on the Brain Bug and Choir in various places.

BS: Can you recall a particular aspect of working on this project your were most fond of?

BP: Fond is probably not the operative word here. Working with Paul and Eric Colvin was the best part of it for me.

BS: You’ve further worked with a director who is quite popular these days: Sam Raimi. And indeed he approached you for a genre (a romantic comedy) that he had never touched before. How did you come to work with him instead of his usual collaborators, e.g. Danny Elfman or Joseph LoDuca?

BP: As with most high profile films, many names are bandied about but I think Danny may have been engaged in another project. I don’t know about Joseph.

BS: In comparison to other directors you’ve worked for, how would you describe Sam Raimi’s take on the role music is supposed to play in the movies? Does he allow enough creative freedom? Does he give the composer any specific hints about what he’s looking for? BS: In comparison to other directors you’ve worked for, how would you describe Sam Raimi’s take on the role music is supposed to play in the movies? Does he allow enough creative freedom? Does he give the composer any specific hints about what he’s looking for?

BP: Sam was very respectful and aware of my desire to contribute to this film and allowed me to do it. He was always very positive and encouraging and with his supportive energy quieted my concern about there being two different versions of the film being edited that both needed to be prepared for scoring, I think that once we set the ground rules that although this was about Baseball which is usually about American Marches and Apple Pie, what we really had here was a bit more introspective psychologically but working itself out on a very large canvass of the playing field.

In the course of one game, we learn about Billy Chapel’s past, and about the fact that he making a decision to retire from the game and whether or not to be with the woman whom he loves. Needless to say, there were many emotions and situations to write music for. Once Sam realized that I understood these parameters, I was pretty much on my own. Although he had a very tight editing schedule, he managed to hear every cue in mock-up form except two. One he didn’t like so we tracked it and on the other he suggested that I put a Choir in the next to last cue to push it over the top. I love choirs, so I appreciated the opportunity to utilize a big one.  BS: Another impressive effort of yours was the result of your collaboration with the renown director John McTiernan. Would you rank ‘The Hunt for Red October’ among the best pieces of music you’ve ever written? BS: Another impressive effort of yours was the result of your collaboration with the renown director John McTiernan. Would you rank ‘The Hunt for Red October’ among the best pieces of music you’ve ever written?

BP: Really good Films inspire really good film scores. Another way to say it is that music never sounds better than it does on a great picture.

BS: What was the source of inspiration you drew from in order to compose your nowadays legendary opening hymn?

BP: The Red Army Chorus to get the feeling of Russian Macho, Prokofiev to get the feeling of Russian Harmony, and Rachmaninoff to get the feeling of the romance of the sea.

BS: One eye-catcher of your musical style is how well you have achieved to manage this blend between the orchestra and synthesisers. Perhaps ‘Wind’ is the clearest example of this. What’s your trick?

BP: Trying to utilize sounds that blend well with the normal acoustic orchestral instruments. I try not to think of the synthesizers as stand alone instruments rather than an organic inclusion to the orchestra.

BS: How would you describe your collaboration with Bille August in ‘Les Miserables’? BS: How would you describe your collaboration with Bille August in ‘Les Miserables’?

BP: Wonderful and unusual. Bille had already mixed the film so his full concentration was on the music. Eric Colvin and I set up a studio in a home in the Hampstead Heath section of London so we could provide Bille with really great sounding mock ups of the final score.

He would come from Sweden once a week and spend an entire day or two listening and commenting on the week’s work. He was very relaxed and wasn’t plagued by the usual exhaustion that most directors exhibit at this stage of the project. As this was a replacement score he also had more of a direction in that he knew what he didn’t want. BS: One particular feature of this score is that it feels less of a classical/melodic effort incomparison to other scores you’ve written. Why did you decide to take this approach?

BP: I wanted to keep the score in the period of the film, if anything, in the style of Berlioz. I tried not to become anymore complicated harmonically or melodically than would have been relevant for that era. It just seems that if an art director and costumer and director of photography and director work hard to create a moment in time, why shouldn’t a composer? There is a reason why we don’t see jet planes or cell phones in 1700 France.

Why should we be subjected to the same kind of intrusions musically? Romanticism wasn’t around yet which may feel as if the melody doesn’t soar nor were Bizet or Wagner with their grand orchestration. One of the goals of the music was to provide a restless urgency or undercurrent to represent the ever-threatened Jean Valjean by Javert.  The other requirement was to keep the temperature medium to cool. This was a directive by Bille and what he was asking was that by not letting the music become overly passionate or romantic that a tension would be created. As if this guilt of Valjean’s was just below the surface and he needed to keep himself in check and not let his emotions betray his feelings. The other requirement was to keep the temperature medium to cool. This was a directive by Bille and what he was asking was that by not letting the music become overly passionate or romantic that a tension would be created. As if this guilt of Valjean’s was just below the surface and he needed to keep himself in check and not let his emotions betray his feelings.

A deceit for sure, but one that he needed to live by to survive. We kept the music from releasing this tension until the very end when Jean Valjean is finally free from the torments of Javert. He has led an honest life and shows us the injustice and cruelty of his times by being virtuous. BS: Did you know before landing on this project that there had been previously another composer, namely Gabriel Yared, attached to it?

BP: Yes. Replacement scores are very difficult for me. Only a composer knows what it takes to write a filmscore and how much of one’s soul and energy goes into it. Replacement scores are usually a sacrificial device when a Studio knows it has a picture that won’t make much money. It often has nothing to do with the quality of the film or the music. It is just the only thing they can change short of reshooting the film. It rarely helps the film. We all know that in the end. I never

spoke with Gabriel as it is oftentimes painful for both composers involved. At least I know that it always is for me when asked to do it.

BS: Simon Wincer is yet another director you’ve worked with quite closely on several occasions. How did you get to meet him? BS: Simon Wincer is yet another director you’ve worked with quite closely on several occasions. How did you get to meet him?

BP: I had just scored Farewell to The King in Budapest and returned home with a cassette of the score. Charles Ryan called me from the Kraft-Ryan Agency which was at ICM at the time. It seems that Simon had gone through all the scores at the agency and was becoming extremely frustrated by what he was hearing. I told Charlie that this was a score written for a WW II saga set in Borneo no less.

He said that I should present a few cues. Simon heard and loved it. I couldn’t believe it and didn’t want to jinx my good fortune but I had to ask what he heard in my music that he responded to. He replied simply, heart. Instead of Copelandesque rhythms and harmonies he was looking for theme as in folk song, which has always been the wellspring which I attempt to emulate when I write any melodic passages. This was also due to John Milius’ insistence on clear, uncomplicated melodies that are not obscure. BS: `Lonesome Dove’ gained you a well-deserved critical recognition and, for many fans, it’s also one of your favourite scores. Do you feel that these ‘Main Titles’ are among the most beautiful ones you’ve ever composed in your prolific career?

BP: The entire score was a joy to write and almost effortless because of the Novel, the Screen Play Adaptation, the Acting, and the Direction of the movie. I am very happy that Simon and I were honoured with Emmies for our efforts but my joy was diminished when Robert Duvall and Tommy Lee Jones, Danny Glover, and Diane Lane were overlooked for their brilliant contributions to the film.

I saw a rough cut of the film in the Producer, Dyson Lovell’s office and loved every frame

of it. I immediately went home to my piano and wrote four of the main themes in less that an hour. This is writing at its best and I knew it was good stuff. No doubts, no hesitations, no editing. Pure flow and energy. I think that my background in American and Scottish and Irish folk songs served me well as well as my own fascination with the Mythic American West. I felt that I born to score this film and will be forever grateful to Simon that he allowed me to.  BS: Again we were asking ourselves is there’s any reason why Simon Wincer hasn’t collaborated with you on all his projects? BS: Again we were asking ourselves is there’s any reason why Simon Wincer hasn’t collaborated with you on all his projects?

BP: Scheduling conflicts arise. I have always refused to score more than 1 film at a time since I write everything myself. Even with the help of an Orchestrator feel that doing two projects at once is a disservice to the Director even if the production entities condone this practice. It becomes too tempting to repeat oneself in the interest of completion instead of taking the time to get it right.

Bear in mind that it might be a chord change or melodic fitting in of a theme that might take hours that one might not have utilized otherwise if they were writing on a very tight schedule. It could be a full orchestra or merely a solo piano but it is only finished when the composer knows that it is no matter how simple or complex. Miklos Rosza considered writing 30 seconds of music a day quite an accomplishment. Compare that to the 5-10 minutes a day required at this time and you might get an idea about were the finer points of composition and development have gotten to.  BS: It seems to us that Eric Colvin has taken over your role as composer for Simon’s Westerns. Do you think we would call him your protégé, so to speak? BS: It seems to us that Eric Colvin has taken over your role as composer for Simon’s Westerns. Do you think we would call him your protégé, so to speak?

BP: I think calling him my protégé would be giving me way too much credit. Eric Colvin was my assistant for about five years but he was a fully defined musician and composer before he came to me. Eric is the most talented musician I have ever worked with. He can work in any style effortlessly and is infected with the joy of making music.

I learned a great from him about the latter day synthesizer technology and advancements in computer oriented writing. Perhaps I shall someday be his protégé! He did gain exposure to all the directors and films I worked on from Celtic Pride to Les Miserables. He was the synthesist and mock up artist on those films and gave me the confidence to make synthesizers sound like an orchestra and free my time for composing instead of being tied down with sequencing. BS: Did you have a chance to listen to his scores for ‘Monte Walsh’ and ‘Crossfire Trail’? What do you think of them?

BP: I think that they are wonderful and meet the requirements and formal dictates of the films. To classify Eric’s music based on these two films would be misleading as he is equally at home in the symphonic, traditional scoring world as he is in the most contemporary of settings. In addition to performing many other instruments, Eric is also an exceptional rock and roll drummer and guitarist.

BS: What has led you to mentor young composers as in the case of Eric?

BP: Because I never had one.

BS: It seems to us that you are now trying to have more time for yourself inorder to be able to enjoy more your own private life. In this sense you might be handing over assignments to composers you’re mentoring. Is that the right impression we have?

BP: As much as it is in my power to do so, yes.

BS: Is there a composer whose work has caught your attention lately? BS: Is there a composer whose work has caught your attention lately?

BP: Along with Eric, I am taken with a young composer named Tobias Enhus. Tobias has a much different approach than I do and is mainly concerned with the experimentation and realization of producing sounds that have a psychological and emotional resonance without necessarily being restricted by any formal harmonic structure or obvious traditional orchestration devices. Many young, computer driven composers utilize this style but Tobias is unique in that he invents his own instruments based upon what he needs to hear coming from within.

This is quite different from buying a CD with samples that only require a composer to push a button and hold down one key to have a musical phrase or looped drum beat or Middle Eastern vocal or God knows what. We all have the same samples and computer instruments (plug-ins). Already, one can hear the boring similarities in many scores that are produced in this fashion. In a sense Tobias is a musical scientist as was Beethoven when he needed to invent something he heard in his head that he called a piano forte. BS: 1996 saw you composing one of your most astounding themes for the Opening Ceremony of the Olympic Games in Atlanta. Did your Greek roots have something to do with you being approach for this assignment?

BP: Absolutely. My father immigrated from Greece as well as both my grandfathers. I wanted to pay homage to my father’s courage and spirit in something so blatantly Greek. Unfortunately, he passed away a month before he got to hear the music or see the spectacle of the opening Dance. My daughter, Alexis, wrote the lyrics in Ancient Greek with a little help from my father.

BS : Mr. Poledouris, thank you very much for the interest you've shown in our interview. We´ll meet you in Ubeda. Good bye.

BP: You are welcome. It's been very nice talking to you, too. I´ll see you in Ubeda.

Interview performed by Jose Luis Díez Chellini

Questions by David Doncel

Additional Questions by Asier G. Senarriaga and Marcus Rip

Transcript by Jose Luis Díez Chellini and Sergio Gorjón

|