|

Trained under Academy Award-winner Jerrry Goldsmith, Christopher Wong is a

young and talented composer whose first film scores for small, independent

Asian American movies have quickly caught the attention of fans worldwide.

Intrigued by his musical skills, this winter BSOSpirit contacted Chris to

unveil some of the mysteries behind his already promising career.

BSOSpirit: We know that you attended UCLA and that it was in college where your interest in film music developed. What we do wonder, however, is if there was already some awareness on your end that movies could become such a nice niche to work in as a composer.

Christopher Wong: I actually had no idea through most of college that I would be working on movies someday. My interest in film music did happen in college, but very late in my studies since it wasn’t until my last semester at UCLA that I met Jerry Goldsmith who encouraged me to pursue film. For a few of my early years at college I probably assumed that I would compose mostly concert music, although upon graduating I ended up becoming involved in both film and musical theatre.

BSOSpirit: Now that you mention it, according to all recounts Jerry Goldsmith played a major role in your training as a film music composer. What was he like in his role of a mentor for young composers?

C.W: This is a difficult question to answer briefly because Jerry Goldsmith really changed my life. I could actually probably do a whole interview on just what I remember about Jerry. What happened was that during my senior year at UCLA, the music department was able to get Jerry to teach 6 private students and I was one of the lucky ones that was chosen. We got to meet with him once a week at his house for a period of about 3 months. C.W: This is a difficult question to answer briefly because Jerry Goldsmith really changed my life. I could actually probably do a whole interview on just what I remember about Jerry. What happened was that during my senior year at UCLA, the music department was able to get Jerry to teach 6 private students and I was one of the lucky ones that was chosen. We got to meet with him once a week at his house for a period of about 3 months.

Jerry was very down to earth during our lessons and I was pleasantly surprised at how he never talked to us as though he was above us, although he had clearly accomplished more than most of us could even hope to. He didn’t like using lofty language and just talked about his experiences in a very unassuming way. He didn’t want to talk about technical stuff like computer software, instead he only wanted to talk about creative and aesthetic issues. Our classes weren’t really like standard college classes, it was more about us asking him a ton of questions and just learning from his wealth of experience.

At the time, he was wrapping up scoring on Star Trek Insurrection, so we got to see him work with a big orchestra at Paramount stage M. Seeing him do that was what really turned me on to working on films--I saw that and decided that I wanted to be able to do that someday. There was also a kind of a paternal side to him that many people don’t know about. By the way he treated me I could tell he believed in me and thought I was talented enough to work in film, which was really what I needed at the time to not be afraid to give it a try.

BSOSpirit: Would you say your music features some of his influences? If so, what would be the elements you consciously refer to when writing a score?

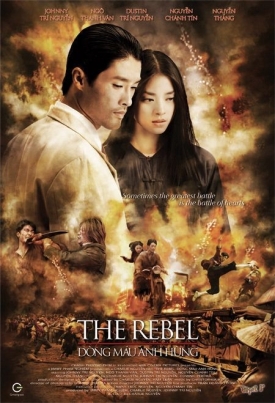

C.W: Well, the score I’ve done that most closely resembles some of Jerry’s style is probably The Rebel (2006),and the funny thing about that score is that I felt very insecure and pressed on time. I had never done an action film before and so I was trying to learn the genre as I was doing it. C.W: Well, the score I’ve done that most closely resembles some of Jerry’s style is probably The Rebel (2006),and the funny thing about that score is that I felt very insecure and pressed on time. I had never done an action film before and so I was trying to learn the genre as I was doing it.

The thing about film scoring that a lot of people don’t realize is that sometimes what’s in your mind is not a deliberation about referencing something musically in a particularly profound way. It’s much more often “Oh my God this score is due in 3 weeks and if I don’t finish this cue today then I’m behind schedule and if I don’t meet the deadline then I’m fired!”

I think because Jerry was my first introduction to the world of film music, whenever I feel stuck on a scene my reaction is to try to think of what Jerry would have done to score the scene. The Rebel, being my first action movie, gave me a lot of scenes where I felt stuck and so I think I probably started imitating Jerry in those scenes. As a result the score has many moments that sound like a Goldsmith homage, which I think Jerry probably would have been a bit flattered and amused by. Much of my other work doesn’t sound stylistically all that much like Jerry, although I probably get a lot of my sensibilities in terms of how music should interact with the picture from him.

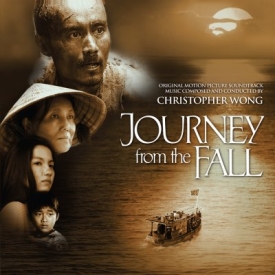

BSOSpirit: For many fans outside the US, Journey from the Fall (2006) was the first opportunity we had to get acquainted with your music. And what a pleasant surprise this was! Unlike some other recent scores, yours avoids conventions. Instead of delivering an impersonal theme, we are faced with this touching, passionate and sincere work. Where does this all come from?

C.W: There are a couple of different aspects to how this score turned out the way it did. Going back to Jerry, one of the great things I remember about our very first lesson is that he asked us to write a 16 bar melody based on a scene he showed us from the film he was working on. No fancy orchestrations or anything, just a convincing theme. That is something that always stayed with me as being important for a film score ever since that lesson.

Fortunately, the director of Journey from the Fall, Ham Tran, felt the same way about film music, he wanted some kind of memorable theme to hold on to. Emotionally, the inspiration came from the story which is based on a compilation of true life experiences of people who were dislocated from their homes and country because of the Vietnam War. Many of my Vietnamese friends have parents, aunts, uncles, and grandparents that actually experienced the hardships depicted in the film, so it wasn’t difficult to feel moved by the story. It just turned out that this particular film and the aesthetic of the director played to my particular strengths as a composer. I feel like most of my natural sensibility in my music is to write lyrically with a tone of melancholy and nostalgia, which was the right fit for this film. Fortunately, the director of Journey from the Fall, Ham Tran, felt the same way about film music, he wanted some kind of memorable theme to hold on to. Emotionally, the inspiration came from the story which is based on a compilation of true life experiences of people who were dislocated from their homes and country because of the Vietnam War. Many of my Vietnamese friends have parents, aunts, uncles, and grandparents that actually experienced the hardships depicted in the film, so it wasn’t difficult to feel moved by the story. It just turned out that this particular film and the aesthetic of the director played to my particular strengths as a composer. I feel like most of my natural sensibility in my music is to write lyrically with a tone of melancholy and nostalgia, which was the right fit for this film.

BSOSpirit: One appealing aspect is how each and every rendition of the main melody feels so different once it is passed through the various solo instruments. Is this a technique that you are particularly fond of?

C.W: Yes actually, I feel like this is one of the most important things to try to do in a film score. Sometimes you don’t always get the opportunity, depending on what the restrictions or freedoms are in the film itself, but I feel that if you are fortunate enough to work on a film that allows you to generate variations on your thematic ideas, you should take advantage of that. In classical music, probably the best model of that is Beethoven, it was just amazing the extent to which he could create variations of his themes. The best model I can think of in film scoring is Max Steiner’s score to Casablanca. Although he didn’t compose the theme to “As Time Goes By,” there are endless variations in his score on that theme and it sounds a little different every time.

In film, a theme should be like a character; we should hear a progression and evolution to the theme just as a good character has a development and an emotional arc. In Journey from the Fall, most of the variations are based on changes in orchestration, although in “Drifting in the Rain” and the end credits track “Journey from the Fall” there is some actual melodic and harmonic variation of the ideas.

BSOSpirit: Another one is surely the ethnicity by means of using the Vietnamese Zither. How did you come up with this idea? Was it easy for you to talk the director into doing this?

C.W: What’s funny is that it was actually the director’s idea to use the Dan Tranh and so he put me in touch with a friend of his who played it. I thought it was a great idea to try to use it and I wish we could have incorporated it a bit more. One of the tracks on the CD is actually a cue from a scene that was cut from the movie, so in the movie we only get to hear it once. C.W: What’s funny is that it was actually the director’s idea to use the Dan Tranh and so he put me in touch with a friend of his who played it. I thought it was a great idea to try to use it and I wish we could have incorporated it a bit more. One of the tracks on the CD is actually a cue from a scene that was cut from the movie, so in the movie we only get to hear it once.

The tough part was that the director didn’t like the way the instrument is traditionally played, which is with the player using lots of glissandi. He thought it sounded too magical when it was played that way, so I kept it simple and had it double the melody. I actually use a little Dan Tranh in The Rebel as well, in a cue that was not included on the soundtrack. It’s a beautiful instrument, but I feel like I’m still trying to learn how to take full advantage of what it can do.

BSOSpirit: Now that we speak about Ham Tran, you two had the opportunity to first work together on his award-winning thesis short-film: The Anniversary (2003). Is he musically trained as well? Do you go into much discussion when working together or is he the kind of guy that rather gives you a blank check?

C.W: Ham and I met in 2002 through a mutual friend from UCLA and we got along really well working on The Anniversary. Ham isn’t a trained musician, although I think he can play a little bit of guitar. He is, however, a huge fan of film music and owns many soundtracks. We discovered early on that we both liked the same kinds of film composers, such as Ennio Morricone and Gabriel Yared.

Ham is extremely interested in how music will integrate into his film and there is always a lot of discussion between us when we are working together. In Journey from the Fall, he had chosen the traditional Vietnamese songs that were to be featured in the film 2 years before any shooting even took place. Sometimes he’ll have a few ideas that won’t quite work, but I will also have a few ideas that end up not working, so our collaborative process is quite involved. We have to arrive at the answers together. Ham is extremely interested in how music will integrate into his film and there is always a lot of discussion between us when we are working together. In Journey from the Fall, he had chosen the traditional Vietnamese songs that were to be featured in the film 2 years before any shooting even took place. Sometimes he’ll have a few ideas that won’t quite work, but I will also have a few ideas that end up not working, so our collaborative process is quite involved. We have to arrive at the answers together.

BSOSpirit: Thanks to Movie Score Media, we just had the chance to come across The Rebel. This score has received many praises, among others, from the Variety magazine that called your music "well-attuned". Are you aware of this? How does it feel to gain such recognition for a small film that won't easily hit a broader audience?

C.W: Since you mention it, I do want to take a moment to recognize Movie Score Media and its executive producer Mikael Carlsson. Although I wasn’t aware of the label when Mikael first contacted me about 2 years ago, I’ve come to realize how important his work is to the film music community.

I’m actually less aware about the impression The Rebel score has made, although I’m glad to hear people are enjoying it. It’s been really incredible to discover that there are people in Spain, for example, that have even heard of me. Since I haven’t gotten to work on any big Hollywood films yet, I usually assume that only a few people will ever hear the music I do for a film like The Rebel. So it’s really incredible that because of Mikael there are people from various places around the world that have heard my music and also the music of the other many talented composers on the Movie Score Media label. I’m actually less aware about the impression The Rebel score has made, although I’m glad to hear people are enjoying it. It’s been really incredible to discover that there are people in Spain, for example, that have even heard of me. Since I haven’t gotten to work on any big Hollywood films yet, I usually assume that only a few people will ever hear the music I do for a film like The Rebel. So it’s really incredible that because of Mikael there are people from various places around the world that have heard my music and also the music of the other many talented composers on the Movie Score Media label.

BSOSpirit: This is a large-scale orchestral score that balances big action cues with smaller, more intimate and melodic moments, thus reminding us that this is, over and above, a love story. You do point it out in the liner notes to the album, but can you tell us a bit more about the creative process you followed to flesh out your ideas?

C.W: The intimate and melodic moments are important in the score not only because that tends to be what I do well, but also because of a conversation director Charlie Nguyen and I had when he was just starting to edit the footage. He told me to remember that at the end of the day the only thing the audience will really care about is how the relationship between Cuong and Thuy will work out.

So, the first thing I did was try to write the love theme for these two characters. I mocked up a demo of it and we put it on top of some footage from the main love scene in the film and Charlie really liked it, so I knew I was on the right track with it. What’s interesting is that there is a second melodic theme which you don’t hear fully until its statement in the alto flute during the first half of the cue “If We Could Forget Who We Are.” This theme was actually intended to reflect a connection between these two characters regarding the back story that each one of them had lost their mothers in very tragic ways. I always thought of it as the “mother theme” when I was working on the score.

However, for reasons of dramatic pacing, the director decided to cut out large segments of the explanation of the back story about Cuong’s mother. Originally, when you hear this theme in the strings in the same cue, it was a monologue explaining this. The scene was re-edited to cut the monologue, but to still fit the music since I’d already recorded it with the orchestra. However, for reasons of dramatic pacing, the director decided to cut out large segments of the explanation of the back story about Cuong’s mother. Originally, when you hear this theme in the strings in the same cue, it was a monologue explaining this. The scene was re-edited to cut the monologue, but to still fit the music since I’d already recorded it with the orchestra.

In all honesty, I’m not sure I had much of a conscious creative process with the action music, since as I explained before I felt I was learning how to do it and if it seemed to work I just felt relieved and moved on to the next piece. In retrospect, I do wish that maybe I’d figured out a way to incorporate one of the melodic themes into the action music a bit more, like what I did at the end of “Motorcycle Escape.”

There’s been a little bit of talk here and there about making a sequel to this movie, so that would be exciting, and I could see if I could work out my ideas more thoroughly. Who knows if and when that would happen, but it would be fun if it did.

BSOSpirit: A distinctive feature of your approach to the action scoring here is that you do refrain from using a single element of programming as opposed to the most common trend nowadays. We guess this wasn't easy given how tight the budget must have been, so why this option?

C.W: Using electronics in action scoring is certainly effective in some films, but I don’t think it would have worked well in this film. The Rebel is clearly set in the 1920’s, and the production design, the cinematography, and even the dialect of Vietnamese spoken in the film was used to reflect a period setting. Usually when I hear electronics, it makes me think of something more contemporary, or even futuristic like The Matrix. Sometimes it is a good choice for other scores, and it even speeds up your work process—I know what a time saver Stylus can be. But I didn’t think it was the right approach for a period film.

BSOSpirit: In that respect, for many critics, some of the action cues are a clear reminder of the style of writing for the thriller scores of the 70s': i.e. the dissonance, the piercing sounds, the use of low end piano lines, vibes and glocks to create rhythm, etc. Was that ever on your agenda?

C.W: The use of the low piano is something I got from Jerry, although I know many other composers do that as well. I think I first noticed it being effective in film by watching Jerry because he was my introduction to the film music world. It’s actually a nice sound to incorporate into the orchestra that was popular with composers like Stravinsky, Copland, and Leonard Bernstein. C.W: The use of the low piano is something I got from Jerry, although I know many other composers do that as well. I think I first noticed it being effective in film by watching Jerry because he was my introduction to the film music world. It’s actually a nice sound to incorporate into the orchestra that was popular with composers like Stravinsky, Copland, and Leonard Bernstein.

Other than that, the specific element that I thought would be fun was getting to use some traditional Vietnamese drums that were loaned to me by a music teacher in Westminster (a large Vietnamese community just south of Los Angeles) named Chau Nguyen. He imported a bunch of these instruments from overseas, so it was really great getting to use them. My friend Pete Nguyen helped me play the drums and arrange some of the parts, and since he’s a much better drummer than I am it was good to have his input.

In general, I also knew that I was going to be extremely pressed on time when recording the orchestra because of our small budget, so I tried to be somewhat modest with the string and brass writing and not make it too difficult to play so that we could record quickly. I pre-recorded all the percussion and piano parts and figured that if they were generating a lot of the motion I would probably be able to cover more ground with the limited time we had with the orchestra.

BSOSpirit: Besides the above-mentioned, are there any other scores - perhaps, less known to the audience- that you feel particularly proud of?

C.W: The first feature I worked on back in 2003 was First Morning, a film directed by Victor Vu who is friends with Ham Tran and Charlie Nguyen. It was shot on a tiny budget and we were all pretty much doing it as a passion project, which sometimes is one of the best situations to learn in. We were all relatively inexperienced and we were all trying to learn how to make a feature together. It was one of those projects where even though I was brought on as the music guy, I ended up recording a little foley and ADR, and did a temp mix of the sound. It was a fun time with a generous schedule and we were just experimenting to see what worked and what didn’t. C.W: The first feature I worked on back in 2003 was First Morning, a film directed by Victor Vu who is friends with Ham Tran and Charlie Nguyen. It was shot on a tiny budget and we were all pretty much doing it as a passion project, which sometimes is one of the best situations to learn in. We were all relatively inexperienced and we were all trying to learn how to make a feature together. It was one of those projects where even though I was brought on as the music guy, I ended up recording a little foley and ADR, and did a temp mix of the sound. It was a fun time with a generous schedule and we were just experimenting to see what worked and what didn’t.

Of course there was no orchestra because there really wasn’t much of a music budget, and so the production value on the score isn’t as nice; it’s mostly synth with some live instrument overdubs and solo passages. I like looking back at that project not so much because I think it’s an amazing score or anything, but more because I do think it was a pretty strong first effort. The scoring has some flaws here and there that I would do differently now, but it has some nice moments as well. It’s kind of like looking back in a diary or maybe watching an old video of yourself playing at a piano recital when you were a kid and thinking, “hmm, that was actually pretty decent for back then!”

BSOSpirit: Are we to see them coming up in the future as CD releases, too?

C.W: Well, a few of the cues from First Morning can actually be found on the Movie Score Media release of Journey from the Fall, although I might feel a little self conscious about releasing the whole thing. Part of it is that the caliber of music and production value on Movie Score Media is so high that I wouldn’t think of asking Mikael to release anything that wasn’t recorded with a real orchestra, or at least mostly recorded with a real orchestra. I’ve been wanting to get back into the studio with a real orchestra again, but because I’m not very well known it’s still hard for me to get those orchestra budgets frequently. Hopefully it’ll happen again soon because that’s what I really enjoy doing. Honestly, I don’t really enjoy working with computers and samples very much, I see it as a necessary means to an end.

BSOSpirit: Outside the film world you seem to be very active as well. Your compositions for full orchestra have been played in the concert hall and you are currently developing a new musical theatre production. Is there an environment you like best? Why so?

C.W: Wow, that musical has been 3 years in development and still isn’t finished!

My background in musical theatre actually mostly comes from working as a theatre accompanist for many children’s musical theatre productions. I’ve really enjoyed watching how theatre teaches kids how to bond and work together to put on a show and express parts of themselves through characters they relate to. I wrote a few musicals in college but they weren’t very elaborately planned out and I wanted to write something where the music was thematically very well threaded through the narrative like in a Sondheim or Bernstein show. My background in musical theatre actually mostly comes from working as a theatre accompanist for many children’s musical theatre productions. I’ve really enjoyed watching how theatre teaches kids how to bond and work together to put on a show and express parts of themselves through characters they relate to. I wrote a few musicals in college but they weren’t very elaborately planned out and I wanted to write something where the music was thematically very well threaded through the narrative like in a Sondheim or Bernstein show.

In this sense, musicals are a bit like film, although the difference is that in theatre you get to perform live in front of an audience and the music actually is actually a primary focus of the experience, whereas in film the music is often not the primary focus. The hard part is that it takes a long time to develop these things and there’s not as much of a financial reward to doing theatre as there is in doing film, unless you somehow end up with a big hit like Les Miserables, Rent, Wicked, or Phantom of the Opera, which is rare.

I heard recently that the production of Gypsy in New York starring Bernadette Peters lost several million dollars, which is discouraging to hear. But I think that is why I like to dabble in a couple of different environments, because there are pro’s and con’s to every genre and often they are contrasting between the different genres. For example, writing concert music, I get to have almost total creative control and during the concert the music is the only focus of the experience.

The problem in concert music is that it targets a very specific and small audience and you really can’t make any money doing it unless you’re someone like John Adams or John Corigliano. Supposedly Philip Glass drove taxis for a while and didn’t really make any money from his music until he was in his 40’s.

Film is almost the opposite, you have to share creative influence in your music with directors, producers, even the movie studio sometimes, and a good number of people watching a movie might not even notice your work. But it does reach a much larger audience in terms of numbers of people and you can get paid pretty well for doing it if you reach a certain point.

Do you ever wonder if Philip Glass wishes he had done a few movies earlier in his career so he didn’t have to drive taxis?

The thing that I don’t like in America, especially within many university settings across the country, is that people think you are supposed to do one thing or the other. People say that this person is a concert composer and that person is a film composer. So when Jerry Goldsmith composes a Berg-ian serialist piece that gets performed by the LA Philharmonic, or John Williams writes a violin concerto, or Howard Shore writes an opera, they are seen as being fake because they are not “concert composers”.

Likewise, concert music fans of John Corigliano see him win an Oscar for composing the film score to The Red Violin, and they discount that score as not being his real music. I’d be willing to bet that any of those composers are proud of their works regardless of what genre it was written for. I’ve never lived in Europe or Asia, but I’ve heard that there is not so much of a stigma against people writing in different genres and environments, which if that’s true I’m very envious of that. Likewise, concert music fans of John Corigliano see him win an Oscar for composing the film score to The Red Violin, and they discount that score as not being his real music. I’d be willing to bet that any of those composers are proud of their works regardless of what genre it was written for. I’ve never lived in Europe or Asia, but I’ve heard that there is not so much of a stigma against people writing in different genres and environments, which if that’s true I’m very envious of that.

Over here, I think most of us think of Toru Takemitsu as a concert composer. But how many of us realize he has almost 100 film credits on IMDB? This guy wrote more film music than a lot of people today that we think of as film composers. Don’t get me wrong, I don’t have any problem with someone being referred to as a concert composer or a film composer as long as it doesn’t come along with an implication that the person doesn’t have any business or ability to try something in another arena.

Anyways, to go back to your original question, I think the point is that I see both advantages and disadvantages to writing in various environments, and so to get to do things in different arenas is a way of having the best of both worlds. I think something that people probably do not know about me is that I’ve written a number of religious works as well, including an Easter Oratorio which narrates the passion week of Christ. It was commissioned and performed by First Baptist Church of West Los Angeles, and was written for a small ensemble of about 7 players and small choir. I’d like to expand it someday for larger orchestral forces if the opportunity arises.

I think that music by nature is a very spiritual thing and some of the greatest classical works -the Requiems of Mozart, Brahms, Verdi, and the St. John and St. Matthew Passions of Bach- are spiritual works. Even a more abstract piece like Messiaen’s Quartet for the End of Time is spiritual in nature. And I know that not all composers are Christian or even religious, but I do think that most composers would agree that music is much more than the notes that are put on the page and that when an orchestra, or rock band, or jazz quartet, or whatever group or soloists play or sing music there is a profundity that goes on far beyond the combination of sound frequencies and timbres that happen to sound good together.

BSOSpirit: Can you talk to us about Pacific Blue Music? What is it? What is your particular role in there?

C.W: At this point, Pacific Blue Music is an informal score production team that includes several longtime friends of mine including Nicole Garcia, my concertmaster and contractor, Ryan Rowles, who does my music prep work, Caroline Kung, who plays all the alto flute passages on my scores and helps me with score coordination issues like booking recording studios, and Emily Rolph, who helps out in a multitude of ways when we are fortunate enough to have her time.

I’m the only composer in the group, although Ryan can orchestrate and arrange, Nicole does a bit of songwriting, and we all kind of dabble in each other’s roles here and there. I’m hoping someday that we’ll be able to frequently offer services to help produce other people’s scores, and once enough business is being made we can be thought of as a full fledged music production company. It’s a company that is a work in progress and I think it’ll be fun to see what we can do for other people’s score production in the future.

BSOSpirit: In addition to Jerry Goldsmith, are there any other film composers that you look up to?

C.W: In general, I tend to be a bit fonder of European film composers, and the way some of them write very lyrically and gracefully are things that I try to emulate. I think Ennio Morricone’s The Mission is probably the best film score to have been written in the past 25 years. So much of his other work is just wonderful also, like Cinema Paradiso and Malena. Gabriel Yared’s English Patient isa favorite of mine, and I think Dario Marianelli’s Pride and Prejudice is tremendous.

The Japanese composer Joe Hisashi is really wonderful, I really like his scores to Princess Mononoke and Howl’s Moving Castle in particular. He has a great thematic variation in Howl’s where he takes a theme that usually presents itself as a Viennese waltz and he gets it to sound like action music, it’s very clever.

I tend to not like the current big Hollywood trend of scoring these days where everything is just loud and huge all the time.

Of the American film composers I do really like, Thomas Newman is one of them. I love how he scores dialogue, the music just lets the film breathe. Another composer that is incredibly unique and gifted is Elliot Goldenthal, although he doesn’t do many films anymore. But of all of them, Morricone for me is the one who has written some themes that are so beautiful and full of longing, like “Gabriel’s Oboe” from The Mission or the love theme from Cinema Paradiso, that it makes my eyes tear up whenever I hear them. It’s almost the same feeling as listening to the Adagietto from Mahler’s 5th Symphony or the middle movement of Ravel’s G Major Piano Concerto. Of the American film composers I do really like, Thomas Newman is one of them. I love how he scores dialogue, the music just lets the film breathe. Another composer that is incredibly unique and gifted is Elliot Goldenthal, although he doesn’t do many films anymore. But of all of them, Morricone for me is the one who has written some themes that are so beautiful and full of longing, like “Gabriel’s Oboe” from The Mission or the love theme from Cinema Paradiso, that it makes my eyes tear up whenever I hear them. It’s almost the same feeling as listening to the Adagietto from Mahler’s 5th Symphony or the middle movement of Ravel’s G Major Piano Concerto.

BSOSpirit: And just to close this interview, would you please let us know what your upcoming film projects are?

C.W: I’m about to do some scoring work on Victor Vu’s new feature Passport to Love which is a romantic drama/comedy. It’s a low budget film, but looks to be pretty good from the footage he’s shown me so far. It’s also a genre I haven’t gotten to write in very much yet, so I’m looking forward to seeing what I can come up with.

Jimmy Pham, who produced The Rebel, has asked me to work on another feature he is in post production on right now called 14 Days. Coincidentally, Ham Tran ended up being the editor on this film, so again I’ll be working with some people I enjoy working with very much.

There’s a film that should hopefully go into production soon called Monk on Fire, which is Dustin Nguyen’s directorial debut. He enjoyed playing the villain in The Rebel, and basically wanted most of the same people that made that movie to be involved in his new film. I’m hopeful that we can get an orchestra for that film, although of course we’ll have to look at the footage and the music budget and decide what’s best for the film.

The nice thing about this community of Vietnamese American directors I’ve worked with is that they haven’t pigeonholed me. I hadn’t done much action and yet Charlie wanted me for The Rebel, and most people wouldn’t think that the composer that did Journey from the Fall would be the guy to call for romantic comedy. They have given me a shot at many different kinds of genres, which I’m thankful for.

Interview and translation by Sergio Gorjón.

|