|

Versión en español

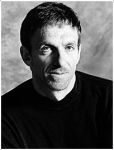

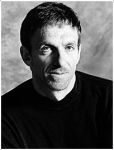

Last March the 20th we were glad to finally talk to Mychael Danna in an interview that lasted more than an hour. In that time we were able to change impressions of his works, his relationship with Atom Egoyan and Ang Lee, and his projects for the near future. Here is that interview.

Seville, March the 20th, 5 P.M (local hour)

A distant bell rings

BSOSpirit(BS): Hi, Can I speak to Mychael Danna?

Danna(D): Speaking.

BS: Hi, this is Sergio calling from Spain.

D: Oh, hi, how are you doing?

BS: Fine, thanks, how you doin'?

D: Fine too, things are good.

So tell me, what's the interview for?

BS: it's for a Spanish web page called BSOSpirit, devoted to film music; and we wanted to make an, in-depth profile of you including this interview as the high point of it.

D: Great.

BS: Ready when you're then.

D: I'm ready.

BS: Then we're going to start with your relationship with Atom Egoyan, if it's okay.

D: Yeah, great.

BS: How did you first met Atom, and how did your professional collaboration with him started?

D: Hang on one second while I switch phones.

BS: Okay.

D: Hi. Hello?

BS: Hi.

D: Can you hear me?

BS: A little far.

D: Hang on one second.

I hope this will work, because you know, I'm packing right now, so I'll talk to you while I'm working.

BS: That's okay.

D: We're actually moving to Los Angeles...

BS: I hear you very far, Mychael.

D: Okay, hang on one second; I'm going to switch phones again.

How about now?

BS: Now is good.

D: Sorry about that.

BS: No problem.

D : So, Atom and I met when we started going to the same university in Toronto. And he was involved in a degree for political science, but he also was involved in the theatre department. He was writing plays and I was writing music for the same department. So that's basically how we met, not in films but in theatre. : So, Atom and I met when we started going to the same university in Toronto. And he was involved in a degree for political science, but he also was involved in the theatre department. He was writing plays and I was writing music for the same department. So that's basically how we met, not in films but in theatre.

BS: Aha, so your film collaboration started as a natural movement from your first encounter in college to time when Atom began to make movies?

D: Exactly, when he finished his degree... I think during it he made a series of small short films, which I was not involved in, but after he finished university, he wanted to make a feature film, so I did the music for that. Neither of us had done a feature film before... I had never written music for a feature film before... so it was the first time for both of us him coming for a theatre background and myself coming from a degree in music composition. Neither of us knew much about film, and certainly we were kind of removed from the popular culture of American feature films; neither of us being really interested or aware of what was going on there. I personally did not really respond to the kind of music that was in American films, especially at that time... so we started working in a way that had nothing to do with that world at all, and it became something quite different.

BS: So working with Atom was much related with your likes in film music and film in general?

D: Yeah, I was very interested in, and have always being interested and still am in music from different time periods, places. And in Atom you could find a person born in Egypt from Armenian parents and he was very interested in middle-eastern music, and very interested in my claim with those ideas; he also was very interested in early music as well so...

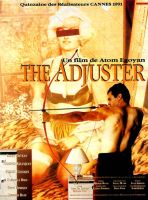

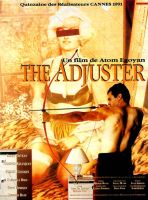

B S:... So that's the time when you work with him in Family Viewings, Speaking Parts or The Adjuster. What kinds of remembrance have you of those old works? Did you have many budgets limitations? Was it a race against time work? S:... So that's the time when you work with him in Family Viewings, Speaking Parts or The Adjuster. What kinds of remembrance have you of those old works? Did you have many budgets limitations? Was it a race against time work?

D: Well, the world of feature film in Canada at that time was kind of a wonderful situation were there was government money, and they certainly weren't big budgets films, but they were government subsidized films to a large extent, so really the artist was left alone to explore wherever things and ideas that he wanted to... so it was really just Atom and me working together a collaboration which has always been and still is a very close one. He gives me the respect and trust and he sincerely likes my work, and I think that makes a huge more easily my work and I find it very inspiring and I think I have done some of my best work for him. And certainly in those early films we were trying to go to different places hadn't been worked on before and we didn't have big budgets to work and most of those early scores didn't have many musicians although I did travel quite often to go recording musicians in different countries. I remember an exotic flying to India to record some musicians. Actually back in those days I would end up spending most of the budget recording the music any way I could, and I really didn't care, I was young and reckless... (laughs)

BS: ...And you liked what you were doing...

D: Yeah, I loved what I was doing and didn't really care of making any money at all...

BS: Relating those first films, Varese Sarabande released an album containing the scores of your first collaborations with Atom, and I would like to focus on a couple of themes that appear on that album. First there's this touching string theme from Speaking Parts?

D: Which one are you referring to? because with all the packing I don't think I can find right now the CD...

BS: Well if not that theme; tell me what you do feel about that soundtrack as a whole...

D: I think the main theme of Speaking Parts, and this is going back a long time ago, but my remembrance is that we wanted something that had a certain kind of fateful mechanism to it, a feeling of movement forward of... of... how can I say this?... kind of cyclic fateful dramatic moving forward and yet kind of always folding back in the distance. And so a minimal treatment was seem to be the best technique, and it was important that this minimalism was able to transport and communicate great and deep feelings, so there's a sense I think in the music of this cyclic fate, and being in the hands of circumstances that are beyond your control and yet there's a great felling of longing and emotion in the very simple melody, which comes up again and again in various guises and orchestrations.

B S: We come to the point when you write Exotica, a soundtrack that boosted your popularity. People began to know some of your trademarks, not only the use of ethnic music, but also the slow and beautiful piano melodies that you like to write. What can you tell us about Exotica? S: We come to the point when you write Exotica, a soundtrack that boosted your popularity. People began to know some of your trademarks, not only the use of ethnic music, but also the slow and beautiful piano melodies that you like to write. What can you tell us about Exotica?

D: I think both Atom and I were able to explore our own personal obsessions through this film. It was a very personal and meaningful work for us, and I think of all the films we've done that's still is the most personal film. I think that the obsessions that both of us have, brought up by him in the film and me in the music, lends the character quite convincingly through the film. I was obsessed with eastern and middle-eastern culture and music at that time...and still am largely (laughs)...so I took my little tiny budget, in fact I remember how much, I think I got paid $4000 Canadian to do that score, and turned them into plane tickets and I just flown around the world with a little tape recorder, I think at that time it was a DAT recorder and a microphone and I just went into whatever strange places I could find and record musicians, street musicians, musicians that I hired as well, but largely music that I found in temples and markets and streets in all kinds of countries. And I think there's a great sense of longing in searching in the music and I think part of it is based on the mechanic of how it was recorded.

B S: From Exotica to Ararat, your most impressive and ambitious work up to date when it comes to your partnership with Atom. What was your approach to the project? In comparison to Exotica, what was the budget you had to bring up the music? S: From Exotica to Ararat, your most impressive and ambitious work up to date when it comes to your partnership with Atom. What was your approach to the project? In comparison to Exotica, what was the budget you had to bring up the music?

D: The budget for Ararat could be easily 50 times the one that we had for Exotica, and hence the difference in the kind of outcome and this obviously is the most deeply personal film for Atom, and also for me, because our friendship goes back so many years now, he's like my brother. All those years that I've known him he had really never talk to me about this part of Armenian history. And when I learned about it by accident many years after I met him, I was shocked and puzzled that he has never...

BS: ...told you before...

D: ...it was very upsetting when I learned about it, and I was very upset that I didn't know and that it wasn't generally known in the world today (Ararat makes reference to the Armenian genocide in 1915). I among others kind of approached him and tried to get him to make a film statement about these events. The producer was a big inspiration and in general it was a labour of love and a very solemn memorial for this event and for these people who lost their lives. Our decision about the concept of the music has to do to the fact that the action of the film takes place almost entirely in Canada, of second generation Armenian and Turks, and the heart of the movie and its soul is back in Armenia, so the music needed to be in Armenia and from Armenia. So Atom and I flew to Armenia in December of (I guess it was) 2001, and recorded musicians and choir there, and then we flew to London and worked with those fantastic western orchestra of 65 players, I think, and... that was most of the budget right there... (laughs). I hoped to make a piece that would be a memorial worthy of these events and of these people, and the music is almost entirely, although there're some pieces that I wrote, folk or church melodies that any Armenian in the world will recognize and will have a very emotional meaning for them. This was a profound experience working on this and travelling to Armenia with Atom and it's a crowning achievement of our collaboration and it means more to me than anything I've ever done.

Don't miss the next episode of our conversation with Mychael Danna, where he is gonna talk about his partnership with Ang Lee, and specially what happened with his rejected score for The Hulk.

By Sergio Benítez and Rubén Sánchezz

|

: So, Atom and I met when we started going to the same university in Toronto. And he was involved in a degree for political science, but he also was involved in the theatre department. He was writing plays and I was writing music for the same department. So that's basically how we met, not in films but in theatre.

: So, Atom and I met when we started going to the same university in Toronto. And he was involved in a degree for political science, but he also was involved in the theatre department. He was writing plays and I was writing music for the same department. So that's basically how we met, not in films but in theatre. S:... So that's the time when you work with him in Family Viewings, Speaking Parts or The Adjuster. What kinds of remembrance have you of those old works? Did you have many budgets limitations? Was it a race against time work?

S:... So that's the time when you work with him in Family Viewings, Speaking Parts or The Adjuster. What kinds of remembrance have you of those old works? Did you have many budgets limitations? Was it a race against time work?

S: We come to the point when you write Exotica, a soundtrack that boosted your popularity. People began to know some of your trademarks, not only the use of ethnic music, but also the slow and beautiful piano melodies that you like to write. What can you tell us about Exotica?

S: We come to the point when you write Exotica, a soundtrack that boosted your popularity. People began to know some of your trademarks, not only the use of ethnic music, but also the slow and beautiful piano melodies that you like to write. What can you tell us about Exotica?

S: From Exotica to Ararat, your most impressive and ambitious work up to date when it comes to your partnership with Atom. What was your approach to the project? In comparison to Exotica, what was the budget you had to bring up the music?

S: From Exotica to Ararat, your most impressive and ambitious work up to date when it comes to your partnership with Atom. What was your approach to the project? In comparison to Exotica, what was the budget you had to bring up the music?