|

Gifted both for scoring a film and cooking a tasty meal, Joel McNeely first drew the attention of a larger audience as the man providing a distinctive voice to a younger version of everyone’s favorite hero: Indiana Jones. After winning an Emmy, Joel McNeely helped expand the Star Wars universe long before prequels became a serious talk. He further dared to try the terror and action genres, ended up working twice with James Cameron and, most recently, he sucesfully mastered Disney´s turf. As a conductor, Joel McNeely is best known for his priceless re-recordings of many Bernard Herrman´s treasured works. Please meet the talented man behind the recipe! Gifted both for scoring a film and cooking a tasty meal, Joel McNeely first drew the attention of a larger audience as the man providing a distinctive voice to a younger version of everyone’s favorite hero: Indiana Jones. After winning an Emmy, Joel McNeely helped expand the Star Wars universe long before prequels became a serious talk. He further dared to try the terror and action genres, ended up working twice with James Cameron and, most recently, he sucesfully mastered Disney´s turf. As a conductor, Joel McNeely is best known for his priceless re-recordings of many Bernard Herrman´s treasured works. Please meet the talented man behind the recipe!

BSOSpirit: You're well-known both as a film composer and as a reputed conductor of other people's work. If you agree, we would like to split this interview into two distinctive parts. The first one will be devoted to speaking about your own original production. Then we will try to focus on your role as conductor in Varèse Sarabande’s re-recordings of music by the likes of Bernard Herrmann and some other film music legends.

Joel McNeely: All right, then.

BS: Let’s start off by travelling to the very early days in your musical upbringing. It is our understanding that you took a few courses at the Interlochen Arts Academy in Michigan where you mainly studied composition and flute. Would you say this played a major role in your late career? Was this the way you wound up involved in jazz?

JM: Well, Interlochen is a very special place to me. You know, I left home and went there really as a kid, when I was 14. So, the opportunity of being there and study music full time was tremendous. Furthermore, this also gave me a chance of meeting there a lot of musicians who were inspiring and accomplished artists. Hence, I guess the short answer is: Yes. This was like getting a head start in compositional training.

And also, as you rightly point out, being a jazz player that’s really what I focused on at Interlochen. But I did take composition as well and so I started the process of learning to compose probably earlier than I would have if I had waited till College. Indeed, I’m still very involved with Interlochen, It was a very important place to me, and now I serve in the Board of Trustees for the School.. so I go up there two or three times a year.

BS: Do you also teach there from time to time?

JM: I usually get Master classes. I’ve been involved in the last 6 years in trying to get a Motion Pictures Arts Major started there. In summer time, Interlochen it’s a very large camp for several thousand of kids and then, in the winter time, the Interlochen Arts Academy goes down to about 400 kids, and that’s for High School reach (9-12).

For those kids you have Music Majors, Dance Majors, Drama Majors, Creative Writing, Photography and Scenic Design Majors; so you have all the different departments that go into making a movie.

Once I got in the Board of Trustees, I thought that combining all these disciplines was sort of a natural step forward, and therefore making a Motion Pictures Arts Major for high school kids seemed like reasonable. Plus in about two weeks they are going to open this new and magnificent building where they are going to host 15 new Film Making Majors with a soundstage, editing studios and a projection theatre. Actually, Interlochen has really evolved from what was really a Music School at first into a fully dimensional Arts School.

BS: It sounds like an exciting project.

JM: Yeah! I mean, imagine this will allow kids to go to a boarding school and earn a Film Making Major at the age of 14! There are going to be some remarkable kids that come out of the programme!

BS: Following your experience at Interlochen you then attended a contemporary-media program at Eastman and, after graduation, you finally started to look for work in film business. However, your growing interest in film music had much to do with your parents, in particular with your father, if we are not wrong. How come that?

JM: Actually, after Interlochen I went first to the University of Miami and then to Graduate School at Eastman.

Indirectly you are right to say that this interest of mine had to do with my father, though it’s more two composers that it all started with rather: Elmer Bernstein and David Shire. My father was a College professor in Wisconsin, but he was active as a writer in Hollywood. He was writing shows for television in Hollywood. So, when I was around 11 or 12 years old he sold a series to the network and they asked him to come out and be executive producer. And, thus, we all moved down to California for a year while he did that.

But before that, when they were working on the pilot, he had hired Elmer Bernstein to compose the music and so, for my birthday, my father flew me out from Wisconsin and I got to go the session where Elmer was conducting the main title for this new show that my dad was doing. Elmer was very gracious and kind. He actually knew I was coming and also that I was a young music student. He had a set of scores copied for me and I got to seat on the podium, next to him and watch him conduct. And I just though this was the most magical thing ever! But before that, when they were working on the pilot, he had hired Elmer Bernstein to compose the music and so, for my birthday, my father flew me out from Wisconsin and I got to go the session where Elmer was conducting the main title for this new show that my dad was doing. Elmer was very gracious and kind. He actually knew I was coming and also that I was a young music student. He had a set of scores copied for me and I got to seat on the podium, next to him and watch him conduct. And I just though this was the most magical thing ever!

Then, a couple of years later, once I was at Interlochen, my dad continued to work in Hollywood and he did many projects with David Shire. And it was again the same sort of thing, i.e. when David Shire knew I was coming he would let me fit in on the sessions and kind of tag along. He gave me copies of the scores and, you know, it was the same story.

So, the first year I moved to Los Angeles after School I contacted David and played him some of my music that I had created. And he thought it was terrific and gave me a job orchestrating the feature that he was doing. This was actually my first job in L.A.!

BS: Not a bad start!

JM: Not at all!

BS: At Eastman you had a chance to study with some very famous composers and orchestrators such as Ray Wright and, if we recall correctly, also Bruce Broughton and David Shire. How do you remember those days? Can you tell us some of the important lessons that you drew from them?

JM: Bruce and David were not at Eastman. They were both well-established composers writing big movie scores by the time I was in School. But Ray Wright was and he was an amazing man! Almost every student that you can talk to would probably say that he was the finest teacher they’ve ever had. He was an incredible composer and arranger plus he knew orchestration like very few people. Indeed, for 30 years he was the head arranger at Radio City Music Hall in New York and wrote several arrangements for a full orchestra every day!

He was actually a great man to study with as he really knew what it was like to be a professional, and he taught you how to be one. He made sure you knew orchestration inside and out, he made sure you learnt how to conduct and how to conduct yourself in a recording session, how to handle a large group of musicians professionally. He was a real inspiration to me.

It’s funny; do you know the music of a jazz composer woman named Maria Schneider? It’s funny; do you know the music of a jazz composer woman named Maria Schneider?

BS: Her name is somehow familiar to us.

JM: She’s, probably, the most prominent jazz composer out there now for writing kind of orchestrally influenced big band jazz. We both studied with Ray and she came to one of my recording sessions here in L.A. once she had been invited by the Mancini Institute as their guest artist. Anyway, the thing is when I came up to her after the session I found out she was crying. And I asked her why and, well, she said that she just had thought of how much this would have made Ray happy, had he seen it. So, you see the students of Ray really kind of look at him in a very special light in their careers. I know I’ve never had a teacher like him before.

BS: Now let’s move to your first scores. In the late 80’s and early 90’s you worked in a number of TV productions which somehow paved the way for you to becoming a real film music composer. How would you describe these first assignments?

JM: My first TV show was a series that I got in 1985 called Our House and I got it indirectly through my father, i.e. through a friend of a friend. And, well, I was kind of not prepared for it. I mean, I did know my way around the orchestra but I was somehow learning how to write.

If I may digress for a moment, let me explain to you that I believe that the art of composition takes decades to learn… at least it did for me. So to get a job after having learnt to compose for a few years in my mid-twenties did imply that I did know some stuff but surely not all I needed to or, let's say, not what I know now. Therefore, when I got this TV show I told them I could do it, but the truth is I didn't know how to do it. You know, in those times, TV scores were all orchestra and you were doing one a week plus writing for a thirty or thirty something piece orchestra. As you can imagine that meant you really had to know what you were doing to crank out that much music every week; you didn't have the time for figuring out how to do it.

So these were two very stressful years in my early TV career since I didn't have any confidence that I could do it and, furthermore, as I was learning on the job I was terrified every week that somebody was just going to find out that I was simply some College kid not knowing what I was doing! Every week I worked unbelievably long hours to try and make sure that everything was written properly so that I wouldn't get fired. It was a real test and not enjoyable at all.

Now it's a lot easier for me to compose, because I feel I've learnt what I didn't know then and how to do it more efficiently. From there on, I went on to do some various TV projects, some movies of the week for Disney... all of them, you know, rather kind of silly, not very well made but they gave me the opportunity to write for larger and larger orchestras which was always what I wanted to do.

BS: Interestingly, many of these projects you've just mentioned were sequels to moderately successful feature films like Splash, Too (1988), Parent Trap III and Parent Trap: Hawaiian Honeymoon (both 1989). It’s probably a funny coincidence but we can’t help asking if there was any particular reason for that?

JM: It was what Disney was doing for the Sunday Night movie shows that they had. These were very cheaply made and, as I said, not very high quality. So it was never like you were working on a piece of art, but rather a means to learn more, to train myself and get experience. Actually it's just impossible to learn what you need to know to become a film composer at School. You just have to learn by doing.

BS: In that period you did also work at least twice in the musical genre thanks to Debbie Allen’s TV movies Polly (1989) and Polly: Coming Home! (1990). How did you handle the challenge of having to deal with a Broadway-style kind of approach to scoring?

JM: Actually it wasn't so much Broadway-style. These were original musicals which, once again, were produced by Disney for the Sunday Movie night that they had. In the case of Polly it came as a result of my very first TV show, Our House, since it was the same producers here.

That was a very nice project as it was a musical set in the South and it had many gospel numbers. My part, however, was not so much gospel but rather more orchestra and, indeed, a very large one if I remember right!

And by the way, the soundtrack to that first one is even plodding around somewhere.

BS: Indeed, we've seen it being auctioned at eBay.

JM: Well, I don't even have a copy of it! (laughs) And I don't even know if I want one!

BS: One of your first feature films was Jackie Chan’s starring vehicle Supercop (1992). This is one of the very few examples of an electronic score by Joel McNeely. Was this influenced by budgetary limitations? Did you like the experience of working with electronics?

JM: Absolutely.

As to the second question, well, I can't say that I don't like working with electronics, but it's just I only like to do it if it's for creative and not merely for budget reasons. Or rather, I'm more like working with electronics in combination with live instruments.

I've spent so much time having to learn how to write for an orchestra properly that writing for electronics is not that all interesting to me. It's getting more interesting now because the equipment is getting more sophisticated and the sounds are better. They are more realistic and playable. Thus, I think now it's more viable as a creative option than just because of having to cut down the budget.

BS: That same year you scored Samantha, a comedy about a girl who on her 21st birthday discovers that she is adopted and sets out to find out who she really is. One relevant element in the plot is certainly the fact that both she and her neighbour do play the violin and the cello, respectively. However, to our surprise your underscore does not too frequently feature either one of these two instruments in a solo performance version. Did you consciously choose to avoid what apparently seemed to be the standard approach to follow?

JM: Hmm, they weren't the same year but they might have come out the same year. I remember that I did Samantha well before Supercop; actually Samantha was my first movie and it was a very fun one to work on. It was again very low budget, but it was close to my heart because it was about a woman who was a violinist and plays on a string quartet and then, as you've just said, finds out that she is adopted. I had such a great time on this movie! JM: Hmm, they weren't the same year but they might have come out the same year. I remember that I did Samantha well before Supercop; actually Samantha was my first movie and it was a very fun one to work on. It was again very low budget, but it was close to my heart because it was about a woman who was a violinist and plays on a string quartet and then, as you've just said, finds out that she is adopted. I had such a great time on this movie!

You know, my wife is a violinist; indeed, she's also playing in the movie! (laughs) And she was also the coach of all the actors. We did all the string quartet rehearsing at our home with our friends and it sort of became a kind of community affair. Plus I love the string quartet, it's one of my favourite ensembles and so to have the chance of writing for a string quartet on my first movie was really fantastic.

And then I took the whole budget and spent it on hiring an orchestra; I didn't get paid on that movie because I really wanted so much for this movie to have an orchestral score. I also felt like I'd love to write one for it. So I spent every penny and even some of my money as I recall on producing that score.

The nice thing was that some people liked it and that Intrada Records was kind enough to put it out in spite of the fact that it was basically a movie that no one had ever heard of. It played in one theatre and went straight to video, so Intrada was only releasing it for the music. I'm sure they didn't expect to sell any copies. And well, that music got around a little bit and led me to other things.

BS: In addition to the classical source music by Mozart, Dvorak and Haydn you also wrote your own ‘classical piece’ for the film: “Mrs. Schtumer's Fifth Symphony”. Is it true that when performed in its quartet format it was actor Dermot Mulroney the one who really played the cello along with Margaret Batier, Julie Gigante and Evan Wilson?

JM: Yes, absolutely. He played all the cello parts in the string quartet. He is a fantastic cellist and not just for an actor, but also for a cellist he is amazing!

The first time we had a rehearsal, he kind of came over and said: "You know, I can play cello pretty well. You might like to see if I could do the recording". And I thought: "Okay, I'll be a nice guy and listen to him play but in the end we'll replace him by a really fine cellist". Now, he comes over and plays at the rehearsal and I was amazed, I was like: "Man, this guy can really play!" If you listen carefully to the cello parts in the string quartet that's not easy play and he plays beautifully!

BS: Before that, you did also work with Tom Shadyac in his first movie as director. The picture was called Frankenstein: The College Years (1991). What was the experience like? Is there any reason that you can tell us about why the two of you have not collaborated ever again afterwards?

JM: We had a really good time! (laughs) This is all electronics, imitating an orchestra as they didn't have any money to hire neither an orchestra nor a choir. And well, I can't tell you why we haven't worked again afterwards. I'd have loved to do so, but he never called! (laughs).

BS: In 1993 you landed on The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles series. Obviously this meant quite a breakthrough in your career. It was also for many film music enthusiasts the score that first caught their attention to your musical universe. Is there any memory you’re particularly fond of that you could share with us? Is there one episode or, perhaps, a given storyline that you remember as particularly daring to write music for?

JM: Oh my God, there are so many!

That was where I really learnt to write because there was so much music in every episode that you really didn't have time to think twice. There was 40 to 45 minutes of score in every one of them and you only had like two weeks to write it. And then, you started another one and then another one again… plus they were all different styles.

So this gave me the chance of really learning how to write to the orchestra. A lot of it was kind of, well, I wouldn't say imitative but they were beautifully but also heavily temp tracked and at the time of editing George would always fashion the temp track as well. So I sort of found myself in a position where all they really wanted me to do was sort of imitate the temp. Certainly I didn't have the confidence as a young composer to say: "This is a great temp but, you know, I could do something different or even better". After all, I was thrilled of working for George Lucas. So this gave me the chance of really learning how to write to the orchestra. A lot of it was kind of, well, I wouldn't say imitative but they were beautifully but also heavily temp tracked and at the time of editing George would always fashion the temp track as well. So I sort of found myself in a position where all they really wanted me to do was sort of imitate the temp. Certainly I didn't have the confidence as a young composer to say: "This is a great temp but, you know, I could do something different or even better". After all, I was thrilled of working for George Lucas.

A lot of times I found myself imitating the temp which, at the same time, was both a good and a bad thing. Good in that I learnt to explore some other composer's music, take it apart, figure out how it worked and reinvent it. And bad in that I wasn't being truly original. So well, now I look back at it and I whished I had had the strength to really kind of have enforced my own ideas then, though I might have been fired after this first episode!

Other special memories are all the travelling. We recorded in Munich, in Australia, in London so we did travel to quite a number of interesting places, and we did further work with many interesting musicians.

And well, there's also the fact of getting to work with the great Larry Rosenthal who is such a brilliant composer. There I was getting side by side with him; what an incredible honour! And well, it was all quite an intimidating situation too, since I was really kind of this kid who didn't know a whole lot of what he was doing and, in spite of all this here I was working with this legendary veteran. But he was always very kind and supportive to the point of being very willing to share his knowledge with me.

Another very exceptional memory I have was getting to be part of the filmmaking when we did 'The Mystery of the Blues' and the Gershwin episode. I was there in the set helping to choose the songs that were to appear in the show. I was also doing the arrangements before they shot and then bringing those arrangements to the set and making sure that they were played properly and that all the musicians were performing in adequate to real. So, well, they gave me this opportunity to hang around and ensure that when an actor was playing the saxophone it looked as if he was really playing it… Perhaps a little bit of trivia right now: Do you know that when we see young Indy playing the saxophone that was always me playing (laughs)?

And then, finally, all this experience of getting to work with George Lucas and Rick McCallum who are two extraordinary filmmakers obviously! And just getting to collaborate and hang out with those guys and learning from them was just an amazing experience!

BS: Now that you've mentioned your collaboration with Laurence Rosenthal, we have realized that in most cases you and Mr. Rosenthal did follow completely separate paths when approaching the series: i.e. each of you worked on your own in a given episode. How did you agree on who was going to write what? Was there ever one episode where you discussed the possibility of splitting the score among the two of you?

JM: As you have just pointed out, we always did our own scores. Actually, they way it happened most times was it came out of the schedule, which means that while one of us was working in one given episode another one would sort of come ready in between and so, the one of us who had already finished his episode first would then start the next one. So, there wasn't a lot of pre-planning but rather it was more a schedule-driven issue.

Also, we never collaborated on the music itself. However, I went to many of the recording sessions for Larry's episodes and simply sat there reading his scores, taking a peak at them and learning what cool things he was doing. This was possible since we would be travelling together to Munich or Australia. And it was like on one day he would record an episode and on the next day it was my turn.

BS: How come you travelled so much to score the series?

JM: Actually, we started off in Munich because they had made an arrangement with a fixer there who was able to get them a very good price for a full symphony orchestra about 70 - 80 pieces; a circumstance that was unheard of for an episode in television. Sometimes we even had a choir!

Therefore we started with the Munich Symphony and then with the Munich Philharmonic and then, through a bizarre trend of relationships and friends with that same fixer in Munich we went to Australia to record. That was fairly weird because it was so remote, so hard to get to. Perth is one of the most geographically remote cities in the world and it took an amazing amount of time, like 26 hours, to get there.

And then there's the issue of London. While we were working in Europe we always used to go back to London to mix and that was pretty cool.

BS: How did it feel to win an Emmy for your work in the episode entitled “Young Indiana Jones and the Scandal of 1920”? To what extent was this award responsible for many of the projects you participated in later on?

JM: Honestly, I don't think so. I really don't know that any award or any kind of awards leads to anything in this town. I certainly haven't seen any evidence of it. However, I must say it was something nice.

Talking about special memories: that evening was one of them. We were there with George Lucas and Rick McCallum and my wife and so she noticed that George didn't have a date. So, immediately, she kind of asked him if he wanted to have one for that night and he said yes. There my wife called at my cousin Donna, a single woman living in Los Angeles and said: "Donna, put on a dress and kick down to Pasadena right away. You're gonna be George Lucas' date." And she came down and we all had a great time and laughed a lot. And afterwards everybody went to a Brazilian jazz bar and stayed up all night celebrating. That was fun!

BS: According to all recounts, it was through John Williams that your involvement in The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles came about. How did it feel to learn that you had such an important composer recommend you?

JM: That's correct. As you can imagine it was a great honour to me. I saw him many times up at the Skywalker ranch when he was there working with Steven Spielberg and I had a chance to visit with him. He actually came to my name because of the Gorfaine-Schwartz agency. He was represented by them and so was I. Apparently George asked John who he wanted to recommend, and he once again asked the agency who they might recommend and they recommended Larry and I.

BS: We are pretty much certain that following the footsteps of John Williams must have been no easy task. Probably you've been asked this many times before, but I guess there's no way we can avoid the obvious question: Wasn't it a bit intimidating?

JM: Yeah, the whole thing was very intimidating, honestly. I was barely 32 years old and had only been working on TV movies. But they seemed to see something in me that they liked and they further seemed to like my work also. So, I kind of simply had to tell myself that this was going to be an incredible learning experience and that I just had to do the best I could.

BS: After the enormous success of The Young Indiana Jones Chronicles' series you then ventured into another one of those George Lucas' project; namely Star Wars: The Shadow of the Empire (1996). This was, once again, one of those scores that most significantly helped you gain exposure early in your career. Would you say that there was more freedom for you to compose given that there was no picture dictating the musical approach?

JM: Certainly… I do have to say that I do have very mixed feelings about that work. I think it was a very cool project, a very interesting idea which was promoted by Bob Townson and the people at Lucas Arts and which, furthermore, George felt to be very thrilling. And so they called me and told me what it was all about and, in the end, someone asked me whether I might like to join in and write an hour of music with no picture for a huge orchestra and choir.

I thought: "Yeah, that sounds like fun!" But then my schedule changed, and two movies I was doing at the time fell on top of Shadows of the Empire. Given that circumstance, I called at Varèse and told them that I was sorry but that I couldn't do it. And then the two movies moved just a tiny little bit and this gave me a two-week window to write; so I wrote one of the movies in a hotel room in Scotland while I was recording Shadow of the Empire.

In many ways I feel it's an opportunity that I kind of lost because I didn't give adequate time to write the music. I listen to it now and I'm not particularly fond of it because everything sounds hurried and I can hear the fact that I wrote it in two weeks. It was a great opportunity and fun to do, but I guess I would have liked to have had a month or even several months to do it in a way that I would be pleased three years after. Now, I only hear the faults.

BS: Well, it's funny to hear you say this as this is a score that has received very good reviews, indeed!

JM: Hmm…. I don't read reviews! (laughs)

BS: Did you ever come to think that you might end up working in the prequels to the classic Star Wars saga after this experience?

JM: No, I didn't. That is such a icon! I mean there's very few other people other than George Lucas that are better identified with Star Wars than John Williams. In other words, if you think about the movies you think of George Lucas first and then, immediately the next person that comes up to your mind is John Williams… that would be more than any movie star!

At least that's what I would say. I don't know. Maybe I'm wrong or maybe I'm saying this because I'm a composer, but he is such an integral part to those movies that it was presumptuous of me to even do the Shadows of the Empire thing. And I always felt very strange about that. Indeed I only went ahead with it because this whole thing was with George Lucas' full endorsement and approval.

That being said, as to working in any of the movies this was never something that I thought of or even something that I would have wanted to do. How could you do anything other than being something less than what the original movies are? Or, alternatively, I could have taken a completely different approach that would have been more identifiable with me but then, this wouldn't have really been Star Wars!

BS: Interestingly your approach is, so-to-say, half-way between Williams well-known style and your very own sensibilities. As was the case with Williams, you also seemed to draw upon the compositions of Shostakovich and other Russian composers of the late 19th and early- to mid-20th century. At the same time, you did also break away from those influences in order to write a score that is more dissonant, hence turning quite unique in its own way. How come that?

JM: Well, in the pieces that were not specifically by John I think there was an attempt on my part to not have them being just a simple imitation of the music he had done for Star Wars. Why do that if I was never going to do it as well as he does it? So I'd say I was trying to inject some of myself and my personal tastes into the rest of it. As to how successful this was, I can't say.

BS: According to the liner notes of the CD, for the vocal parts of the score you chose to develop a language of your own. Was it your idea? Was this the way to mark a departure from the music that had been written for the original saga?

JM: I didn't develop this language. I went to Ben Burt, the great sound designer and editor who has worked in all the Star Wars movies. He is a friend and he pretty much developed all the languages through Star Wars. So, I called him up and said: "Hey, I need some text". I told him what I was thinking and he sent me some stuff which was again based on all of the languages of Star Wars that he had developed.

I added some of the words I have to say, because they didn't necessarily fit the phrases that I wanted. So, if there's anybody who speaks Jabbar or anything it might not make any sense to them! (laughs).

We had fun doing it, though. A lot of the words are just English words spelled backwards. We were really trying to work with a choral text which is, essentially, nonsense because they are very free, you don't have to worry about syllables. If you want to change a phrase, you simply change a word. (laughs).

BS: More or less in between these two major projects you also participated in a number of films which, for many film music enthusiasts, provided you with the opportunity of writing some of your most memorable themes to date. Take, e.g., Iron Will (1994): a rousing orchestral score that turns out to be another major character in the movie. Here your music does cover a wide range of emotions and styles. Is such a heterogeneous score a big challenge for you as a composer?

JM: This was continuing the round that I had done in Young Indy. It wasn't a big budget movie, but it was certainly my first movie that wasn't a low, low budget movie. So they had the money to score adequately with a large orchestra and, I guess, it therefore turned out to be my first real movie, so-to-say.

The director Charles Haid loves music and had all kinds of pre-conceived notions of what he wanted ,and they fortunately matched what I wanted to do: i.e. ,to make music be a large part of telling the story. He gave me a big canvas to work with and it was an enormously fun movie to work on.

BS: One very much discussed issue about Iron Will is the impact that temp tracks might have had in the final result. Was this the case?

JM: Oh yeah. There's one very important scene there which was tracked with the opening or… well, I'm not sure which cue it was but it definitely was from Silverado. I wrote something completely different for it and after they had screened it for the executives of the studio they went: "No, no, no. We want that big thing we had in the temp". So I had to go back and recompose something more like Silverado which is something that I really didn't enjoy doing but had to. And I called Bruce Broughton and told him what was going on and he was very nice and said: "Oh, I had to do that, too. Don't worry about it."

The fact that it went up on the record, that's kind of bothersome because anybody that knows both those pieces may go like: "This guy is just a copycat". But in my defence I have to say that it was either do that or not be the composer on the film.

BS: Does it happen to you frequently?

JM: It doesn't happen to me as much anymore because the older I've gotten the more secure I am as an artist. And I realize you can say no to that sort of thing and, maybe, you should say no. But when you're young and you're just starting a career, you don't want to make anybody angry at you. You just want to give them what they want. So you don't have the courage or the moral conviction to go: "That's not right. I'm not going to do it." All you want to do is get another movie so you can keep going.

As you go down the road you realize: "Oh, maybe the better thing to do is to stay true to your own artistic ideas, and maybe they'll respect you for that." So, I don't do that anymore. I don't play that temp track game. (laughs)

In fact I try not to listen to the temp tracks of the movies I work on now. Indeed, I think if I had to do over these things again, I absolutely would never give into that temptation or direction from filmmakers. I would at least work hard to try to convince them that having something original for your movie is better than having something that imitates something else. And not all filmmakers would be persuaded from the beginning, they'd go: "Yes, but this piece of music works perfectly." Then you should try and write something that works as well. And even so, filmmakers may get stuck on their initial idea. That's fine, I understand that but it's certainly a creative trap for a composer. In fact I try not to listen to the temp tracks of the movies I work on now. Indeed, I think if I had to do over these things again, I absolutely would never give into that temptation or direction from filmmakers. I would at least work hard to try to convince them that having something original for your movie is better than having something that imitates something else. And not all filmmakers would be persuaded from the beginning, they'd go: "Yes, but this piece of music works perfectly." Then you should try and write something that works as well. And even so, filmmakers may get stuck on their initial idea. That's fine, I understand that but it's certainly a creative trap for a composer.

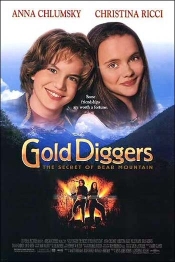

BS: This was also the period were you did Wild America (1997), Flipper (1996) and Gold Diggers: The Secret of Bear Mountain (1995), all of them so-called family films, that deal with stories about youngsters forced to face incredible adventures. Do you have a special interest in these type of films? Are they particularly attractive in terms of the potential musical approach that they do offer?

JM: You know, I've never chosen a movie to work on in my entire life. They choose me! (laughs). I pretty much take everything that is offered to me. There are composers out there who pick and choose what they do. I'm not one of them. I haven't been that lucky. So, when you say you chose the project, I shall rather say I was lucky enough to be at it. Fortunately they were nice movies and nice people, which is always important to me. I had small children at the time and, well, at least in the case of Wild America that's a movie that my kids still want to watch, so it's fun when you can work with something that's enjoyable for your children and certainly satisfying, too.

BS: Actually, now that we are talking about Wild America one issue that has always struck us about the soundtrack album is the apparently poor sound quality of the recording. There’s cues where you score does sound very distant to the point that several parts of it are hardly recognisable. Can you shed some light on what happened?

JM: Oh my dear, you should see how the original sounds! (laughs) It was recorded by Shawn Murphy, I'm sure you know who Shawn Murphy is, and the original sound was amazing. Then the Studio, when it came the time to master it, hired this guy, this bumpkin who had some kind of way-out digital process that he was going to put through. You can read in the album that it was done with some super something process that I don't know what it is. I think he did like two or three records and every one he did, he made the sound so incredibly horrible that he never worked again.

So, when I first got this thing I couldn't believe how bad it sounded. I couldn't even listen to one cut. And I called them up and said: "What have you done to my music!" And they went like: "Oh, we like it." And then I got this huge box from the record company that they were nice enough to send me like, a hundred of these things… And I was like: "What am I going to do with this. I can't even listen to it." So, ultimately they ended up in the trash can.

What a tremendous waste! So nice of the record company to put that out but for God's sake why wouldn't they give the artist approval over how it was mastered? That's beyond me. So much money was spent there with good engineering and good playing… That was always kind of a sad point for me because you can't go back.

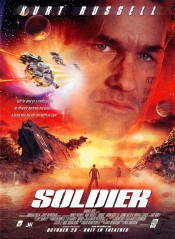

In the same way, although for different reasons, I feel about the Soldier soundtrack. This was nobody's fault. The story behind here was that for Varèse's production reasons the CD needed to be mastered before the score was finished. We actually had another two weeks of recording beyond when the CD was mastered. So, most of the best music in the score hadn't been recorded yet. In the same way, although for different reasons, I feel about the Soldier soundtrack. This was nobody's fault. The story behind here was that for Varèse's production reasons the CD needed to be mastered before the score was finished. We actually had another two weeks of recording beyond when the CD was mastered. So, most of the best music in the score hadn't been recorded yet.

When it came time to put together the CD for the score it was not what I wanted at all, and it wound up being not a very good listen, kind of aggressive and unpleasant. There was some really more beautiful and intimate sleeping music. So, that was pity for all of us. I wish I could take these things back.

BS: Now that you mention Soldier we were wondering if this the reason why the soundtrack is so short?

JM: Yes, that's one of the reasons and then there's also the fact that re-issue fees were very high at the time and they had to keep it under half an hour. Anyhow, I'm sure that Bob would have worked that out had we had that extra music. There's an end credits suite that's the best thing of the score and, unfortunately, it's not on the record. Actually, in my opinion all of the best score is not on the record. So, yes, it's very frustrating.

BS: As to Gold Diggers: The Secret of Bear Mountain, we feel it is a very good example of the type of rousing adventure music that fans so often await in your scores. Interestingly, orchestration-wise there’s not just these huge string and brass sections all over the score but also quite a number of tender moments thanks to some very beautiful guitar solos. This brings us to the question of the role your orchestrators play. You have often worked with the likes of David Slonaker, Chris Boardman and Art Kempel, among others. What is it they bring to your music?

JM: Of the three you mention, I have a long association only with David Slonaker. Chris Boardman and Art Kempel I worked in one score with and, as you probably know, the latter one passed away two years ago. He was a great composer by the way… an amazing one.

Dave Slonaker has been, so-to-say, my partner in orchestration for almost twenty years now. We went to Eastman together and we both studied with Ray Wright, so we had the same kind of training and we were brought up the same way. He is an amazing musician and an amazing orchestrator. Dave Slonaker has been, so-to-say, my partner in orchestration for almost twenty years now. We went to Eastman together and we both studied with Ray Wright, so we had the same kind of training and we were brought up the same way. He is an amazing musician and an amazing orchestrator.

I give him more than most composers he works with. I give him very complete sketches like, say, three lines of woodwinds, four lines of brass, five lines of percussion, two lines of piano and harp… it’s almost a complete score what I give him. But what he brings to it is really checking it and putting it on the big paper, making sure everything is balanced properly and so kind of backing me up. For example, if I ever write something that sound funny or comic he comes and asks me whether I really meant to do this.

He is a real knowledgeable orchestrator because he knows his classical music inside and out. Sometimes, we’ll both go over a score to see whether a certain balance will work and will put, e.g. some Tchaikovsky as was the case in this last score we did. So we’ll just check each other.

He has just been a great colleague to work with all the twenty years, as somebody who can make sure that my work is presented in the best possible way when we get before the orchestra; i.e. that there are no mistakes, that everything is completely professional and that the sessions go as smoothly as they can. And fortunately for Dave he has started to work for many huge composers. He stays very busy.

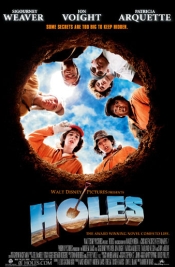

BS: Almost a decade after the previous film, you returned again to the very same Disney-esque turf with the picture Holes (2003). And again your music was very much celebrated. Unfortunately, in spite of the many good reviews there was finally no commercially available soundtrack album with your score. You must be aware that there’s a lot of people out there who want to have this soundtrack.

JM: Oh, I didn’t know! JM: Oh, I didn’t know!

BS: Yes, indeed. That’s why we wonder if we can we expect this to ever happen in the future?

JM: Well, this is another one of those… You know, you seem to find all the sore spots in my career! (laughs).

I’ll tell you exactly what happened: now the Studio has a policy of not having two conflicting products after the same movie. They first had a CD full of all the songs to the movie which they wanted to put out and they had told me that six months after they could possibly put out a score CD to coincide with the DVD release. But when it was time to the DVD release the song soundtrack was still selling so strong that they didn’t want to confuse consumers in having two different albums out there and, well, I was not allowed to release it. So, I was very sorry that it didn’t get out there.

Unfortunately, this has happened to me many times, most recently twice a couple of years. So, I doubt that a record company would find it profitable right now to put it out after the film has passed, though it would be great to have this music out there.

BS: Do you ever have a chance to suggest that this or the other score you have written might have a market if released?

JM: I always try to get a release but recently, with the animated movies I've been doing with Disney it's back to that same policy. In other words, Walt Disney Records does not want to be in the business, at least for children's records, of putting out score albums. And they told me this.

I did two movies for them last year that are two of the best scores I've ever done and neither one of them is ever going to be released. And that happens as well with the Heffalump movie which I think is maybe one of my very best scores. That would have made a great record!

I wish they would allow the composer to put them up on iTunes so that people would kind of decide whether they do want the song album or the underscore one. People can certainly make the distinction.

Anyway, I'm not yet done fighting so I'll let you know! I'm trying to schedule a meeting with the record company to see if I can convince them to release some of my recent scores. You know, I did this movie called The Fox and the Hound 2 this year which was just so fun… I worked with some of the greatest bluegrass musicians in the world and it was just fantastic. There's so much music that I'm certain people would love. And, well, this time they only let me put two pieces in the record and they were very small ensemble. One was just me playing solo piano, and the other was a small bluegrass piece, but there's some great orchestral stuff in the score, none of which will be in the record, sadly. Anyway, I'm not yet done fighting so I'll let you know! I'm trying to schedule a meeting with the record company to see if I can convince them to release some of my recent scores. You know, I did this movie called The Fox and the Hound 2 this year which was just so fun… I worked with some of the greatest bluegrass musicians in the world and it was just fantastic. There's so much music that I'm certain people would love. And, well, this time they only let me put two pieces in the record and they were very small ensemble. One was just me playing solo piano, and the other was a small bluegrass piece, but there's some great orchestral stuff in the score, none of which will be in the record, sadly.

BS: Now that you mention animation films, this is indeed another particular field you've grown us accustomed to see you working in lately. Your name has been attached to quite a number of sequels to some of Disney's most renowned classics. Can you tell us something about how you started the said collaboration?

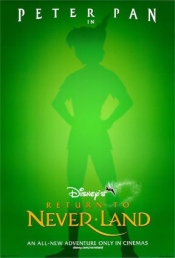

JM: That's due to my work with Disney Toon Studios and that up until last year was their business model, i.e. making sequels. I made a conscious choice when I did Return to Neverland to start working with them because really wanted to do something that would involve my family, which means something creatively satisfying but also something that my kids could enjoy.

At Disney Toon I found an environment that I still believe is completely unique in this business in that from the President of the Division, Sharon Morrill, to the President of the Music Department, Matt Walker, they believe in the power of the score and budget it in a way where we can do huge scores to these tiny little movies. They really protected the music budget, so it's amazing to realize that of the 5 or 6 movies I've done with them we've had budgets equal to and sometimes even larger than those of big feature films as respect the music department, but they are only 15 to 20 million dollar films.

It was a real pleasure working with them and they really respected the value that a live orchestra brings to their production. You listen to so many movies, some of them direct to video, that are going on now and they are sampled orchestra. But the one good thing about Disney is that they are aware of the difference and how this gives you a sense of quality, class, size, etc. So, I have to say I feel like I found a little home.

The only instruction I ever got was: “Write the best you can and we'll give you budget and time to do it!” They traditionally allow me two months to write a score and a full week with a huge orchestra to record it. That's unheard of now.

However, since there are no soundtracks I guess people don't have the slightest idea of what we are doing there, but I still hope that folks that are soundtrack fans may listen to it at the movies. Actually, I'm more proud of this than of anything else I've ever done.

BS: Indeed we believe this is often the case. Take, e.g. your score for Return to Neverland (2002). This was positively greeted by many fans. And it came as a very nice surprise to the audiences since the movie didn’t seem to have so much material to work on. How come this score was so huge?

JM: That's because we never took the attitude that these are little sequels. We always say: "Let's shoot for the moon! Let's do it as well as we can!" And I think that shows.

The last film of this kind I finished for them was Cinderella movie, and all the musicians that played on it came up and they were almost crying at the end of the sessions because they were so happy to be given something to really play. You know, it's like having a Ferrari and most of the time it gets driven 5 mph around the racetrack and then somebody says: "O.k. let's open it up and let's go full speed."

These are highly trained musicians that hardly get to play anymore. So we came in with this very old school score, really calling back to Korngold and music of that era, and so the brass players were just exhausted by the end of the day! They never get to play in that style anymore.

It was really fun. Again, I wish I could get a release.

BS: When working at sequels like the ones you mention, do you ever feel somehow confine to re-use previously existing themes from the original picture?

JM: Occasionally. For example in the case of Return to Neverland we referenced to all the themes in first picture and that was basically it. But what I do have to reference thematically sometimes are the songs in that particular film, like in the Heffalump movie. There I worked with Carly Simon and she had written several wonderful songs for that movie which I would sporadically reference in my score.

BS: Back again in the area of live-action feature films, you’ve also been responsible for some very remarkable action and sci-fi/horror scores. There’s actually three titles that we would like to ask you a few questions about: The Avengers (1998), Soldier (1998) and Virus (1999). According to all recounts, The Avengers was a troubled production from the outset. Michael Kamen, who had been initially assigned to the project had to leave after 8 months, and so you came on board. When this opportunity arose you were in London for some few more re-recordings for Varèse. Is that correct?

JM: Yes. We were in London working on… I think it was Torn Curtain, and then we re-scheduled to go back up to Glasgow and do a week of recording up there. That’s when the event just happened and I had to get out of going back to Glasgow. So, this is when John Debney came in and he set for me taking over these recordings in Glasgow. It was literally a phone call one day and all of the sudden I had to jump on The Avengers.

BS: Given what you have just told us, it’s obvious that time pressure must have been huge but the end results are, indeed, outstanding from the point of view of your fans…

JM: Thank you. I like this score a lot. I’m very fond of it and also of the movie. The movie that I originally saw and started to work on was a very different one than the movie that was finally released. There was a big tag of war back and forth between whether to make this movie more suitable for American audiences or something that would appeal to an English sense of humour given that this is a story that had a big British sensibility. So, the movie in its original form was kind of more true to the original and I though delightful. Then towards the end it became more kind of designed for an American audience and so, maybe it wasn’t as successful by that point as it might have been. Anyhow, I still think this is a delightful movie in whatever form.

I had a great time working on it. I loved the director Jeremiah Chechik. He kind of let me do what I wanted to do which is kind of a jazz and fused, retro spy score with smudgy Bond-type influences and also some kind of fantasy to it. It was a very fun movie to be working in. It had so many crazy things going on all the time... Like these whole flights of the mechanical bees that were trying to kill them, or this really fun chase sequences, etc.

BS: How about your work in Virus? What do you recall of it?

JM: Virus is the first horror movie that I wrote a score for. I also had fun with it. I mean I loved playing with orchestral textures and colors, integrating some synthesizer sounds in with the orchestra. It was really challenging!

And again, big orchestra at Abbey Road with Shawn Murphy: that's pretty great! Any day you are doing that it's a good day!

BS: In spite of the lengthy sections of dark and hardly audible underscore, your music for Virus is better known among film music enthusiasts for its occasional orchestral outbursts and, in particular, for the military march performed by a Russian choir in the end credits suite. What was the source of inspiration for such a magnificent theme?

JM: None that I do remember other than its Russian crew and the Russian ship. I just decided to use a male chorus, but I don't believe it was inspired by any particular canticle but rather just an idea I had.

Now that I think about this… you were talking earlier about the lyrics and texts in Shadows of the Empire. Well, here what they are singing is like the names of my colleagues but backwards. You know, David Slonaker spelled backwards. (laughs)

BS: It’s true that the chorus is also visible in some other cues throughout score, but one can’t help thinking that you might have envisaged to use it even more often. Was this the case?

JM: Gosh, it's been so long since I did this score, I don't really recall now.

You are right that there's not a lot of choir in there. In thinking back, I believe that the chorus thematically represented in my mind terrestrial life, i.e. the reality of the men and women on that Russian ship. But once the ship gets taken over by the alien being, it was no longer a human ship, so I didn't want to have human voices in the score to sort of ground it in terrestrial reality.

I think that the only time I used the choir in the score was at the very beginning of the movie and then at the very end. Anytime we were in the alien world, I didn't use it and played rather with form and texture.

BS: There's also another side of your career that is of particular interest to us as is namely your collaboration with James Cameron: once for the TV series Dark Angel (2000) and then another time for the IMAX documentary Ghosts of the Abyss (2003). How did you land on these projects?

JM: I'm sure some of my music that was submitted for these projects made into his office, and he obviously heard it. But then again it was through my agent and also due to the music supervisor on Dark Angel, the latter of whom was very instrumental in getting me on it. So, I was very lucky to work with him twice. Both times very different, but equally interesting. JM: I'm sure some of my music that was submitted for these projects made into his office, and he obviously heard it. But then again it was through my agent and also due to the music supervisor on Dark Angel, the latter of whom was very instrumental in getting me on it. So, I was very lucky to work with him twice. Both times very different, but equally interesting.

The pilot to Dark Angel was mostly orchestral score and then it became kind of a synth thing that I generated out of my own studio. And then Ghost of the Abyss was, I'd say, half and half.

He is a very specific director to work with because he does know exactly what he wants for music. He is willing to listen to your creative input and he does not often come with many preconceived notions, i.e. he is creatively open. But if you say: "Hey, check this out", he knows immediately if that will work for him or not. I mean immediately; he doesn't need to think and he will go like: "Yes, this is right for this reason or no, this is not right for this reason". He is kind of a wickedly smart guy!

BS: By the way, both Dark Angel and Ghosts of the Abyss have fuelled speculations about your likely participation in either one of James Cameron’s future projects. Any news that you can share with us in that front?

JM: I'm not aware that people are speculating but I'm certainly speculating myself, hopeful that I would get a chance to work with him again! (laughs)

BS: Let's hope we can see you working in some of these projects. BS: Let's hope we can see you working in some of these projects.

JM: Yeah, let's hope. Call him up! (laughs)

BS: Just a final word on Dark Angel. Your innovative approach to the series makes us think that you somehow anticipated many of the musical trends that have later settled down in other action-packed vehicles like, e.g. Alias. Do you consider yourself a pioneer in this respect?

JM: Gosh, I don’t' know. That's for other people to judge.

I was always a little bit frustrated that more people didn't pay attention to the music of Dark Angel, because I felt it was kind of different. Maybe it was just people didn't like, but the fact that Jim didn't put any creative restrictions on it helped me take it sometimes really far out. It a pity because I never got the sense that people thought about it in one way or another as I never got any feedback on this at all.

At least we were trying to do something a little different. Actually, I got a rerun the other night after so many years of not having thought about it. I was simply flipping through the channels and there it was. So, I watched it and I just kind of laid there laughing because I kind of thought: "Man, that music is so kind of out there! How did they ever approved that!" (laughs) It's really strange stuff like this one whole queue where I was playing the saxophone, and then I put it to all kinds of crazy filters and play it backwards. That's all I used: backwards saxophone! That was really weird.

BS: Since we have just spoken about your TV work once again, we wouldn’t like to miss the opportunity to mention what’s perhaps the two most delightful scores you’ve ever written: Sally Hemmings: An American Scandal (2000)and Lover’s Prayer (1999). Both are period dramas featuring your typical orchestral sensibilities in combination with the musical flavour of the period. Did you spend much time researching the musical influences of the period?

JM: Absolutely! For Sally Hemmings I studied a lot of music of the XVIII century; classical music. And before that, I also studied music from Corelli such as the Concerti Grossi. Actually, leaving in a household where my wife is a very accomplished classical musician I do get a lot of my education through her. She is a concertizing violinist and so, most of this music I somehow learn to know because of her.

As to Lover's Prayer, this was something special because this was a TV movie, not a show. It was done by a director who was really very much trusting in my own decisions. I just wrote a theme that I played for him in the piano and he went like: "Yeah, that's great!" Then I told him that we were to record this with the London Chamber Orchestra and he said: "O.k. Have a good time, I don't really feel like going to London. I trust you." So this was the only recording session I've done for a movie where nobody from the movie was there!

Which means that we got to do exactly what we wanted to and, as a result, the recording sessions weren't really of the type of what would work or not for the picture, but it was rather more about how could we make this phrase more beautiful. Or about what we could do with dynamics to make this be interesting. So, I was sort of working more as a conductor than as a composer there. I felt like rehearsing for a concert. And the sessions were so enjoyable simply because they were all about the music. Which means that we got to do exactly what we wanted to and, as a result, the recording sessions weren't really of the type of what would work or not for the picture, but it was rather more about how could we make this phrase more beautiful. Or about what we could do with dynamics to make this be interesting. So, I was sort of working more as a conductor than as a composer there. I felt like rehearsing for a concert. And the sessions were so enjoyable simply because they were all about the music.

I guess this is one of my favourite scores for this reason. It was the only time where we were just completely left on our own to do exactly what we wanted to do with the music. And I think you can hear that. I mean it's certainly one of the most personal works that I've ever written. No temp track at all, no referring to anything else: just the music that I wrote.

This score has a very special place in my heart!

End of the interview 1st part.

Interview performed and transcripted by Sergio Gorjón

Questions by Sergio Gorjón, Asier G. Senarriaga and Juan Antonio Martín Martín |