|

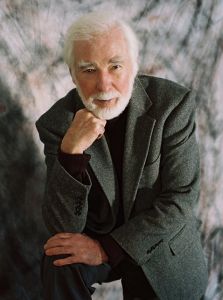

With a career spanning over several decades, John Scott has proven to be a

one-of-a-kind composer whose unparallel commitment to his true passion,

music, has left us countless cherished memories. Last summer John Scott took

a break from the preparations of his forthcoming film music concert with the

Hollywood Symphony Orchestra in order to speak with us lengthy about his

past, present and future life in films. With a career spanning over several decades, John Scott has proven to be a

one-of-a-kind composer whose unparallel commitment to his true passion,

music, has left us countless cherished memories. Last summer John Scott took

a break from the preparations of his forthcoming film music concert with the

Hollywood Symphony Orchestra in order to speak with us lengthy about his

past, present and future life in films.

Join us in the first part of our interview to John Scott.

BSOSpirit (BS): According to your biography, your first assignment to score a motion picture was the horror movie A Study in Terror (1968). However, you seem to have had some previous experience composing for films like in All Night Long (1961) -an updated version of Shakespeare's Othello- as well as in the short film Fragment (1965), directed by your long time collaborator and friend Norman J. Warren. How do you remember these early experiences?

John Scott (JS): You are quite right. I had gained a certain amount of experience composing music for documentary films and one of those films Shellerama was produced by Dimitri De Grunwald. This is when I met Norman J Warren who worked for Dimitri as an assistant director. At that time Norman was working on his first film entitled Fragments. He asked me if I would like to compose the music for his film and I agreed. From that time Norman J Warren and I have remained very close friends.

By the way, I was more an actor in the film All Night Long. The film featured jazz musicians taking part. I got to write one piece which I was seen playing in the film, and I played all the saxophone solos which the star Keith Michell was seen to be playing. I also got to play with the great Dave Brubeck. However, at that time it was a dream of mine to write film scores.

BS: By the number of times you and Mr. Warren made pictures together, one might say you both were able to find the 'ideal partner'. How come you have not worked more frequently with other directors?

JS: All I can say is that I was a late starter in the field of film composing. I had always been a performer, at the time I met Norman Warren I was still known more as a performer than a composer. It was a couple of years later that I was forced to consider becoming a film composer. By that time most composers were teamed up with directors and I was still unknown. Of course I had composed music for documentaries and Norman and I had established a good relationship but we both had similar problems finding work.

It is always a case of "who you know" rather than "what you know"! I feel that, had we both had the good fortune, we would have worked well together. As it is we probably did some 10 films and all were very good experiences and very rewarding.

BS: Most of these pictures with Mr. Warren were part of the wave of British indie horror flicks that gained momentum in the 70's and early 80's. Interestingly, due to censorship restrictions in the UK, some pictures like Satan's Slave (1976) or Inseminoid (1981) were shot in two versions: one, let's say lighter, for domestic distribution and another one, perhaps tougher, for foreign markets. Were you ever asked to also write down different versions of your themes? If so, how was that experience? BS: Most of these pictures with Mr. Warren were part of the wave of British indie horror flicks that gained momentum in the 70's and early 80's. Interestingly, due to censorship restrictions in the UK, some pictures like Satan's Slave (1976) or Inseminoid (1981) were shot in two versions: one, let's say lighter, for domestic distribution and another one, perhaps tougher, for foreign markets. Were you ever asked to also write down different versions of your themes? If so, how was that experience?

JS: I cannot recall having been asked to write different versions of any film for Norman J. Warren, however Norman was a great editor as well as director and would have dealt with any such problem. We never had the luxury of recording two versions of anything. JS: I cannot recall having been asked to write different versions of any film for Norman J. Warren, however Norman was a great editor as well as director and would have dealt with any such problem. We never had the luxury of recording two versions of anything.

BS: Now, turning again to the movie A Study in Terror (1968), if we are not wrong you were about 37 when you landed on it. As you've told us before, by that time you were already an accredited player who had, moreover, been often working on pictures with the likes of John Barry and Henry Mancini. What took you so long to finally get to move to the next level?

JS: As a playing musician I was always in demand. I enjoyed performing, and I also ran a jazz quintet. I wanted to do everything. People tended to regard me as a performer and, as such, I did not have a high profile as a composer. It was because of having worked on a documentary for Dimitri de Grunwald, as I've already said, that I was finally noticed by Herman Cohen who engaged me to compose music for his film A Study in Terror.

BS: The fact that an extended version of this former score was newly recorded by the Hollywood Symphony Orchestra a short time ago makes us think that this Sherlock Holmes vs. Jack the Ripper vehicle may have a special place in your heart. Is that so? How was it to be in command of a larger ensemble of musicians for the first time? BS: The fact that an extended version of this former score was newly recorded by the Hollywood Symphony Orchestra a short time ago makes us think that this Sherlock Holmes vs. Jack the Ripper vehicle may have a special place in your heart. Is that so? How was it to be in command of a larger ensemble of musicians for the first time?

JS: Of course my first feature film must have a special place in my heart. It was a great thrill and a big move in my career. Nevertheless I had often worked with orchestras of the size of the Study in Terror orchestra which was 40 musicians. I believe the music for Shellerama, the documentary which brought me to the notice of Herman Cohen, was composed for an orchestra of approximately 40 musicians.

BS: Your production for the horror genre seems, nonetheless, to overall avoid recurring to the now-so-common dissonances and pulsing patterns of this type of films. Take, e.g. the case of Witchcraft (1992): here, instead of following the archetypal approach, you clearly took advantage of the entire orchestra to play over suspense, menace and even tenderness. Do you consciously try to stay away from the more conventional formulas or rather is it your musical upbringing that explains this circumstance?

JS: I have not consciously stayed away from dissonance in music. I love violent and dramatic music, but I have made a conscious effort not to copy what other people are writing. I now have confidence to know that I have my own musical language, so why resort to copying other styles? JS: I have not consciously stayed away from dissonance in music. I love violent and dramatic music, but I have made a conscious effort not to copy what other people are writing. I now have confidence to know that I have my own musical language, so why resort to copying other styles?

Unfortunately, today the music industry makes a demand on composers to copy temp tracks and scores from successful films. I refuse to work under those conditions. I sincerely hope that things will change and composers will be allowed to be creative once more.

BS: If you were to rank your own scores, we are positive Antony & Cleopatra (1972) would be placed quite atop of the list. This is also the case for most film music enthusiasts who often find this one to be the utmost example of a thematically strong score with no few daunting moments. Drawing basically upon both, the astonishing 'Love Theme' and 'Cleopatra's Theme', you managed to create a dazzling score that virtually plays action and emotions in all possible ways. Where did this inspiration come from?

JS: I was honestly nervous composing the music for Antony and Cleopatra. I had a very short amount of time, probably a month, and it was a long film with a lot of different types of music. It was also the first time I had worked with a full symphony orchestra and large choir. I feel lucky that it turned out so well. After that I gained a lot of confidence. JS: I was honestly nervous composing the music for Antony and Cleopatra. I had a very short amount of time, probably a month, and it was a long film with a lot of different types of music. It was also the first time I had worked with a full symphony orchestra and large choir. I feel lucky that it turned out so well. After that I gained a lot of confidence.

Recently I composed a 45 minute work based on the original score, but incorporating 3 actors who delivered the Shakespeare text. I had the chance to rewrite and improve the orchestration, but found that I did not need to rewrite or improve, and so it remained the same. We performed it live in concert in Los Angeles and it was a great success.

BS: The re-recording you made back in 1992 with the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra and Voices was warmly greeted since it has certainly given many of us the opportunity to enjoy this instant classic with perfect sound quality. Originally it was the London Symphony Orchestra and Choirs that played your music. Why did you choose to go over recording this particular score once again and release a new album with more music?

JS: The recording you are talking about was recorded at different times. I could not afford to rerecord it at the same time. However, when it was released I thought I had recorded the whole score until someone told me that I had left one important cue out. I rerecorded the missing cue "The Egyptian Bacchanal" in Los Angeles and re-mastered the CD which we then re-issued. We also had a chance to improve the cover and artwork.

I am very happy that we were able to include the missing cue. It has since become very popular on concerts.

BS: The 80's saw you creating some of the biggest highlights in your career. One of people's all-time favourites -Greystoke: The Legend of Tarzan, Lord of the Apes (1984)- dates back to those days, but there¹s further quite a number of pictures you worked in that sport remarkable scores by John Scott: King Kong Lives (1986), Man on Fire (1987) and Shoot to Kill (1988), just to name a few. Was this a particular fruitful period in terms of the quality of the films you were offered to work in?

JS: This period was a fruitful period! It might have carried on but for the fact that my mother became ill with Alzheimer's disease. This meant that I had to leave Hollywood and return to London and look after her until she died. I do not regret this, it gave me the chance to think more about music outside of films.

I composed a number of works for chamber groups including my first string quartet, which is extremely important to me. When I finally returned to America my connections had been taken over by other composers and I did not like the kind of films that were being offered to me.

BS: If you don't mind, we'd like to spend a little bit more time speaking about some of the soundtracks of that period. Let's start with The Final Countdown (1980). A rousing score recently re-released on your own label, this is often talked to be the first major breakthrough of your career. It has a catchy and powerful militaristic main title that no single fan can forget. Is it true that some critics disapproved your music because they felt it sounded like the propaganda tunes used in your local recruiting office? BS: If you don't mind, we'd like to spend a little bit more time speaking about some of the soundtracks of that period. Let's start with The Final Countdown (1980). A rousing score recently re-released on your own label, this is often talked to be the first major breakthrough of your career. It has a catchy and powerful militaristic main title that no single fan can forget. Is it true that some critics disapproved your music because they felt it sounded like the propaganda tunes used in your local recruiting office?

JS: I do not know about the remarks you mention. I do know that you cannot please everybody. There is always going to be somebody that disapproves. All I can do is try to do my best. It must also be true of any artist, that some things are more acceptable than others.

I enjoyed writing the score to The Final Countdown. It was a thrilling film to work on, and it was thrilling to spend some time on the aircraft carrier "USS Nimitz" and eat with the captain and meet the flyers of those incredible aircraft, and to actually have them put on a display for Kirk Douglas, Katherine Ross, Martin Sheen and myself. We composers do not get invited out that often. We just sit in our little room with a piano and manuscript paper and then, one day, we come to a recording studio and record the score. It's quite lonely sometimes.

BS: How come Rachel Portman was credited along you in 1982's film Experience Preferred ... But Not Essential? How did you manage to create a seamless experience to the listener having two different composers working at once? BS: How come Rachel Portman was credited along you in 1982's film Experience Preferred ... But Not Essential? How did you manage to create a seamless experience to the listener having two different composers working at once?

JS: All I can tell you about Experience Preferred is that David Putnam, the producer of that film, liked Rachel Portman and wanted her to compose the score. I seem to remember providing some songs. This is very unusual for me, but I was working with a lyricist called Malcolm Hillier. We did a lot of commercials together and somehow or another some of our songs got into the film. I cannot remember if I contributed to the underscore or not.

BS: Yor, the Hunter from the Future's (1983) Kaa-Laa Dance provides an ethnically-flavoured, percussion-driven theme. How come you went on taking this approach at a time where similar pictures were following a radically different style?

JS: I think I have answered this question: Why should I do what other people are doing? I can only be myself. JS: I think I have answered this question: Why should I do what other people are doing? I can only be myself.

The film was a bit embarrassing for me because after it had been finished and everybody was happy, they decided to go with an Italian pop song score. A lot of my music was left in but it made no sense to me. I used to get telephone calls from people asking why this music was there and had I really written this pop music score?

BS: The actual album to this score closes with a 20-minutes suite. It's virtually a showcase of all possible styles: from distinctively elegant melodies to some very fast-paced action cues; let alone not forget some surprisingly experimental efforts here and then. Why did you choose to make this arrangement for the album instead of keeping themes apart? BS: The actual album to this score closes with a 20-minutes suite. It's virtually a showcase of all possible styles: from distinctively elegant melodies to some very fast-paced action cues; let alone not forget some surprisingly experimental efforts here and then. Why did you choose to make this arrangement for the album instead of keeping themes apart?

JS: You must be talking about an album put out by John Lasher on his own label "Southern Cross". I can only imagine that John Lasher decided to edit the sequence in that fashion. He did contact me to tell me that he intended to issue the album. The music was recorded in Rome and the orchestra had some difficulties.

I was told that because the orchestra was a large orchestra the musicians union insisted on some students being booked for the sessions. I warned the musicians that they should look at a couple of cues which were a little more difficult. When we came to record them the orchestra was technically inadequate and I refused to conduct until they were ready. I sat in the control room and waited until the orchestral manager called me. They played much better after that. If ever I get the chance I will rerecord the score.

BS: Greystoke: The Legend of Tarzan, Lord of the Apes is probably your best known American film. It displays a ravishing score of exquisite grace that you've often play in concert. The film production was somehow controversial when original screenwriter Robert Towne withdrew his name from the credits after having failed to direct the picture. Hugh Hudson, of Chariots of Fire fame, came to replace him. Did this turmoil affect you in any way? How come your name was attached to this production?

JS: You know so much more than I do! I did not know anything about Robert Towne's involvement, nor do I get into politics if I can avoid them. JS: You know so much more than I do! I did not know anything about Robert Towne's involvement, nor do I get into politics if I can avoid them.

When I was a playing musician I used to compose music for Hugh Hudson's commercials. I was hired to compose the Greystoke score because of Hudson's recommendation. It was an extremely difficult film to score and they had already had two attempts. One with a composer I will not mention and another score which was assembled out of classical music and specially recorded by the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra (RPO). The Royal Philharmonic manager suggested my name to Hudson who then recommended me to Warner Brothers. I had enjoyed an ongoing relationship with the RPO because of Jacques Cousteau. We used to record Cousteau¹s music with that orchestra.

BS: The fact that half the film (the jungle part) does hardly feature any dialogue must have been a great challenge for you as a musician. It was just your score plus sound effects that had to put the audience in the right mood! Was this a major reason for you to accept the project?

JS: The reason I accepted the assignment to compose the Greystoke score was because I was offered the chance to compose a satisfying score. The real bonus was being able to work with such a fine orchestra.

The first half of the film, with no intelligible dialogue, was only one of many challenges. I think the biggest challenge was that Hudson wanted a tragic score. When he briefed me he said he wanted an operatic score in the manner of Wagner's Tristan and Isolde. Warner Brothers wanted Superman in the Jungle. They were briefing me in exactly the opposite way to Hudson's brief.

I had to decide that Hudson was my boss. In fact, I did write a cue for when Tarzan becomes king after vanquishing the ape leader. After we played the cue with the picture the whole orchestra burst into applause. I was very happy until Hudson told me he did not want that effect. He made me rewrite the cue. This time it was more vicious and primitive, and Hudson was happy, and the Warner Brothers' executives were disappointed. I was really in a no win situation.

BS: Your music to A Shooting Party (1985) is indeed another major character in the movie. It has the refinement of the English School and, as such, it works very well in order to depict the lives of the privileged. Did you have to devote much time to study the work of the old English masters?

JS: The Shooting Party was one of the easiest scored I have ever composed. Somehow it just flowed out of me. No, I did not have to study the English School, in fact I think that the film itself, which is very English, inflicted its character on the music. JS: The Shooting Party was one of the easiest scored I have ever composed. Somehow it just flowed out of me. No, I did not have to study the English School, in fact I think that the film itself, which is very English, inflicted its character on the music.

When people used to ask me how I composed music for Cousteau's underwater films I came to realize that it is the emotion that you have to get right, after that the visual aspect of the film has a way of colouring the music.

BS: The JOS album has further the added bonus of delivering your score to Hugh Hudson's 1965 documentary Birds and Planes. In spite of the obvious budgetary limitations, the outcome is pretty much interesting. How do you remember the early collaboration between you and Mr. Hudson?

JS: I used to think that Hugh Hudson had one of the finest eyes for detail on the screen. He used to spend hours getting the visuals right; in commercials one had the time to do that. He took this gift into everything he produced. He was equally exacting about the music. That suited me and I really admire most of our collaborations.

Birds and Planes was a stunning documentary. The idea behind it was to contrast all kinds of planes with all kinds of birds: helicopters with humming birds, gliders with condors, jet planes with frigate birds, cargo planes with pelicans. Get the idea? He gave me a free hand to compose the music for this film and I composed a score which was inspired by Hudson's imagery.

I used a very classical but unusual group of instruments: a string quartet, piano, and 4 string basses. The sombre quality of the basses and the percussive nature of the piano was my idea of the mechanical (soulless quality) of the machines, while the singing quality of the piano in the high register, and intimacy of the string quartet represented life and nature. This was a most gratifying commission, and it was just a 15 minute industrial documentary.

BS: John Guillermin's sequel to his very own 1976 remake of the classic King Kong movie had you facing the risk of being measured against your friend John Barry (who was in charge of the original film's score). Did this ever deter you from accepting the project? Was your friendship with this composer one of the reasons you were chosen for this assignment? To what extent were you asked to achieve certain continuity with the previous score?

JS: John Barry was a person with whom I developed a close relationship based on mutual respect. I started working with John Barry early in his career when he had a weekly TV series with his own group the "John Barry Seven". I was recognized as the top jazz flute exponent and saxophone player in England and he invited me to be a regular guest, playing my own brand of jazz, with his group.

At that time I had never considered the thought of composing as a career. Later I played on his first film Beat Girl and still later I played on his wonderful Lion in Winter and the James Bond scores. He always regarded me as a featured soloist within his written scores. When he recorded the King Kong film I was just starting to compose seriously. At that time I had never considered the thought of composing as a career. Later I played on his first film Beat Girl and still later I played on his wonderful Lion in Winter and the James Bond scores. He always regarded me as a featured soloist within his written scores. When he recorded the King Kong film I was just starting to compose seriously.

It was after Greystoke that I was approached to compose the music for King Kong Lives. John Guillermin was the director and I met him in North Carolina where he was shooting King Kong Lives. We did not discuss John Barry and I was given the impression that he was looking for another kind of score, a more human score. His first King Kong was a remake of the original, this was an extension. He briefed me very carefully and very exactly as to what he wanted the music to do in his film. Luckily I did not have to copy or use any of John Barry's musical themes.

BS: Man on Fire is another brilliant film score by John Scott. To us, it features one of the most memorable main themes you've ever written. One of its strengths is how wisely it does balance high-powered action pieces with the more affectionate moments in the plot. The different renditions of the main theme (grandiose, trendy and subtle as in 'Reunion') are simply an unambiguous testimony to your skills as both composer and orchestrator. But there's quite more to this score. In particular we were wondering why didn't you make a more extensive use of the Latino-flavoured element as was the case with cues like "Starting the Search"?

JS: All I can say is that it has never been easy for me to compose a score for a film. Shooting Party was an exception. I compose many themes before I feel that I have found enough suitable material which might, or might not be a starting point. Gradually I allow the film to dictate to me how the music will help, and what it is going to say. In other words the music becomes an organic part of the film. I also truly feel that the function of music in films is to support and amplify the visual and emotion aspects. It should grow out of the film. Only at times should music dominate. I am of the opinion that the best film music is generally invisible because it is doing the right job by enhancing the visual experience without saying: "Hey! Listen to me, aren't I clever?" JS: All I can say is that it has never been easy for me to compose a score for a film. Shooting Party was an exception. I compose many themes before I feel that I have found enough suitable material which might, or might not be a starting point. Gradually I allow the film to dictate to me how the music will help, and what it is going to say. In other words the music becomes an organic part of the film. I also truly feel that the function of music in films is to support and amplify the visual and emotion aspects. It should grow out of the film. Only at times should music dominate. I am of the opinion that the best film music is generally invisible because it is doing the right job by enhancing the visual experience without saying: "Hey! Listen to me, aren't I clever?"

Why did I not make more extensive use of the Latino-flavoured "Starting the Search"? I honestly don't know the answer to your question. Had it been suggested at the time I'm sure I would have considered it. In this case I was working very much on my own. The director was in Switzerland, the producer was in Los Angeles and I was in London.

BS: Luckily a score album was released by Varese Sarabande at the time the film premiered, but it's been long out of print. Indeed, it's become quite a rarity these days and whenever it gets auctioned on eBay it's virtually impossible to grab a copy below 100$. Is there a chance that JOS Records will ever re-release it again, perhaps with more music?

JS: I will look into the possibility of releasing Man on Fire on the JOS label. It is becoming increasingly more and more difficult to cover the cost of manufacture and recover the costs owing to the fact that regular record sources are being driven out of business because of World Wide Web practices and piracy.

BS: Have you seen the remake that Tony Scott directed a few years ago starring Denzel Washington? What do you think of Harry Gregson-Williams' music?

JS: No I have not seen Tony Scott's remake of Man on Fire, but I think that Harry Gregson-Williams is a very talented composer and, if he is allowed to be creative, we can expect some great scores from him in the future.

BS: Shoot to Kill was an adventure thriller movie where an FBI agent (Sidney Poitier's comeback after a 10 years break) was faced with the task of tracking a psychopathic killer across the mountains in New England. The score is a perfect blend of the more operatic qualities of some of your early output, on the one hand, and the jazzy tunes that you later developed in Lionheart (1990). Was your approach influenced by the fact that this was, so to say, an "outdoor film"?

JS: I remember in this film that Director Roger Spottiswoode was most keen on having a one theme score. I was not in total agreement, but I had to listen to my director and take notice. JS: I remember in this film that Director Roger Spottiswoode was most keen on having a one theme score. I was not in total agreement, but I had to listen to my director and take notice.

Remembering my jazz roots and the fact that we were going to record this film in Los Angeles, the land of my jazz heroes, I decided to use jazz in the score. I settled on a certain jazz saxophone sound which had not been used, to my knowledge, for some time. I had the very best jazz musicians at my disposal and took advantage of that fact. It was very satisfying for me to go back to my roots and, even though the score is a one melody score, I was able to achieve variation through orchestration. The one time when I tried to introduce a new theme for a new element I was chastised by the director and had to rewrite the cue.

BS: We are sure you must be aware of the legion of film music enthusiasts that are longing to see this score definitely being released. It seems the announcement was made long time ago but still no specific deadline has been disclosed on the JOS site. What can you tell us about this?

JS: Would you believe me if I were to tell you that we have been trying to negotiate with the legal department of the film company, and it is very difficult. It is easier for the bootleggers to do things illegally. I do hope that we will get permission at a price that is sensible. This is the difficulty.

Nowadays the artwork has to be paid for, a license has to be paid for and then the company might say that we are not allowed to use the title or the names of the stars on our CD cover. After that the musicians have to be paid again, or the music has to be rerecorded. I personally would rather do a re-recording because then we can get a better performance without having to be in perfect synchronization with the film. As you know, the big record companies only issue big box office film soundtracks.

BS: Just to close the decade, you offered us what for many fans was seen as a surprising assignment for John Scott: Lionheart. Listening to you score, one has the feeling that here it was somehow the "Johnny Scott Quintet" coming back to work! Probably, one of the most intriguing aspects of your music lies in the way the main theme was divided into two parts that only came together once Van Damme's character found his inner strength. Did you have this approach very clear from the start? BS: Just to close the decade, you offered us what for many fans was seen as a surprising assignment for John Scott: Lionheart. Listening to you score, one has the feeling that here it was somehow the "Johnny Scott Quintet" coming back to work! Probably, one of the most intriguing aspects of your music lies in the way the main theme was divided into two parts that only came together once Van Damme's character found his inner strength. Did you have this approach very clear from the start?

JS: Lionheart was a film I have been criticized for accepting. Why should John Scott interest himself in composing for a kick boxing film? I have to say that the thought never occurred to me. I liked the emotion of the film. I really enjoyed the challenge of the development of the character. I enjoyed the variety - from urban city drugs to Foreign Legion - street fighting to big organized fixed fights. I loved the fact that there was an ethnic quality bestowed on the fights. I loved the idea that the ethnic quality was amplified and echoed through the musical score. Last but not least I purposely intended the theme to grow from nothing in a tentative way and gain strength as the main character matured and for that tentative theme to finally emerge as a mature theme complementing the mature spirit of Lionheart.

Follow us in the second part of this interview, to know more about John Scott's career from 90's and so on, as far as his collaboration with Jacques Cousteau.

On behalf of BSOSpirit we'd also like to express our gratitude to Mr. Otto Vavrin II for his valuable assistance in preparing and arranging this interview.

Questions by Sergio Gorjón & Asier G. Senarriaga.

Interview performed by Sergio Gorjón.

|