|

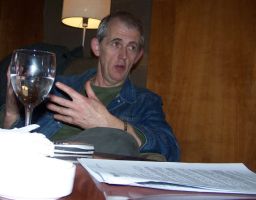

Better known for his sweeping romantic scores such as his Award-winning

music for "Shakespeare in Love", Stephen Warbeck is an eclectic musican

with a taste for World-Music whose interests have brought him to work on

quite many diverse productions over the years. Better known for his sweeping romantic scores such as his Award-winning

music for "Shakespeare in Love", Stephen Warbeck is an eclectic musican

with a taste for World-Music whose interests have brought him to work on

quite many diverse productions over the years.

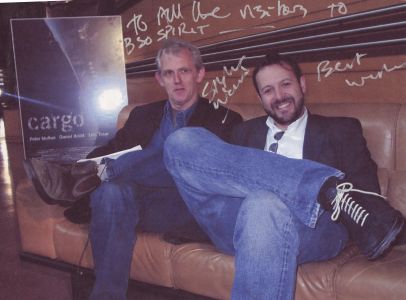

Last Winter, BSOSpirit had an opportunity to interview this

multifaceted composer whose views on films and music we now want to share

with you all.

BSOSpirit (BS): How did you end up scoring music for films?

Stephen Warbeck (SW): I always enjoyed film music, indeed I was often listening to music in films; but my very first score came together when a director I knew from the theatre asked me to make a movie about a dance school. It was a bit like Billy Elliott, but before Billy Elliott, right in 1984. The story was about a group of children from Northern England learning to dance and was called Happy Feet.

BS: How do you explain your visibly classical style?

SW: I don't think of my style as of a classical nature. It somehow depends on what you listen to, like say Birthday Girl, that's quite not classical at all.

Certainly, on the one hand, my music is influenced by classical composers, but on the other there's also rock, jazz and many other styles that I've come to take advantage of.

Maybe the kind of music that has become more visible is what you call classical or romantic but only half my production does fit into this concept. It's not the use of an orchestra what makes it classical.

BS: One of your first scores was written for the series' Prime Suspect, shown in UK TV. How do you remember that experience? BS: One of your first scores was written for the series' Prime Suspect, shown in UK TV. How do you remember that experience?

SW: Well now that you mention it, I recall that the choreographer on the film Happy Feet was married to the director of Prime Suspect, so I guess it must have been her who got me this other job somehow. I remember I had a very strange feeling when working on that series. This was a very dark police television series, quite serious drama! And I couldn't really belief I was doing it as it was the very first big thing I was ever involved in!. In fact, I still harbored very pure ideas about what you would do and what you wouldn't do in writing music. I felt as if I was betraying my ethical convictions of not merging into that tradition of tough police series which can be very popular but too violent... This is still my feeling. Maybe there's too much police series on TV.

BS: Other projects during this period included The Mother, The Changeling, Bambino Mio or Devil's Advocate. To what extent do you consider that these projects influenced your subsequent opportunities in the film industry? Had you already met John Madden at that point?

SW: That's how the story goes: most of TV series script-writers or directors want to become future film directors, so their dreamed projects went together with mine. We started a relationship of mutual interest. But I don't remember thinking of entering those projects because of what they could mean for my career later on. It was rather they seemed very interesting to me because of one reason or another. SW: That's how the story goes: most of TV series script-writers or directors want to become future film directors, so their dreamed projects went together with mine. We started a relationship of mutual interest. But I don't remember thinking of entering those projects because of what they could mean for my career later on. It was rather they seemed very interesting to me because of one reason or another.

In addition most of the pieces you mention were single projects, i.e a single picture for TV which meant that we did approach them in very much the same way as you would do for a motion picture.

As to John Madden, he did direct one Prime Suspect show and two television films I did, so this is where our colaboration began, 19 years ago.

BS: With Mrs. Brown, film music fans started harvesting some awareness about you. How did you decide what musical approach to take in such a particular love story, a real life love story? BS: With Mrs. Brown, film music fans started harvesting some awareness about you. How did you decide what musical approach to take in such a particular love story, a real life love story?

SW: I did my best to understand the relationship that was being portrait as one of a love which never was. Indeed it's a story about a disappointed love, so I mainly tried to focus on the concept of a potential love for my music. Now, in terms of scale of the score, resources were limited. This was a BBC film and I only had three weeks to write it.

BS: In your subsequent collaboration with John Madden you achieved general acknowledgment as well as awards, in particular, that well-deserved Oscar in the category of Best Music, Original Musical or Comedy Score. The film was, of course, Shakespeare in Love. Was it a difficult task? How did you cope with that huge variety of emotions present in the film?

SW: I didn't really try to write separate music for each character but instead I rather approached the film paying attention to the love story between Shakespeare and Violet, which is why you have this very romantic central theme. Indeed, it's not just this theme but also quite some other themes that were written with that in mind, sort of capturing the emotional aspect of the love affair between the poet and his love interest.

BS: One of your following assignments, Mystery Men, had a soundtrack that didn't see an album release. Your score, however, had some very good moments, approaching the superhero universe. How was it like to be involved in this film? BS: One of your following assignments, Mystery Men, had a soundtrack that didn't see an album release. Your score, however, had some very good moments, approaching the superhero universe. How was it like to be involved in this film?

SW: Well, I have to tell you that I haven't seen it! To be honest, I don't think this was a good film at all. Many changes were made on the run, and the final result wasn't brilliant.

BS: Shirley Walker was also involved in that project, writing additional music. Did you meet her? Did you give her any particular indications?

SW: No, because we worked on the music separately.

BS: The film was indeed a commercial failure and it had very bad reviews. Was this perception further exported to the musical aspect of the picture, which would explain why the score was finally overlooked by record labels?

SW: I don't know. Initially the film seemed as a good idea, the freshness of something different, very eccentric with less of a stupid superheroes side, so I felt like I could have a lot of fun in doing something very different to what I had done before.

I remember that the original film had a huge amount of scenes with Geoffrey Rush and Lena Olin, some very good ones indeed. And then they did a test preview in California to a younger audience and they started to cut some of the weirdest parts. So two months before the film was released, I saw it and it still was very mad and then they just tried to make it a more straight comedy type of film, so finally the original formula evolved into a strange animal.

As to releasing my music, well I don't think so but I'm still quite unaware of what CDs of mine are running around. Last week in Berlin someone came up to me with three CDs and I didn't even know they did exist, like e.g. Love's Brother!

BS: In 1999, you came back to the TV with A Christmas Carol, based on a book by Charles Dickens. Personally, we believe that marked a return to your creative roots. BS: In 1999, you came back to the TV with A Christmas Carol, based on a book by Charles Dickens. Personally, we believe that marked a return to your creative roots.

SW: Somehow it did but it was unintentional. The director approached me and, well, I had always liked the story and I knew it very well since it's a very interesting piece of writing. I felt very comfortable with the idea of writing music for such a nice tale, a universal story and, well, I was and still am doing other things outside film music: I've worked for TV a couple of times since, I do a lot of theatre, etc. It was just that I thought this was something I wanted to do and the director was also a very nice person to work with, so that's how it came out to be.

BS: We cannot forget your contribution to Billy Elliott, a really big success, both commercially and from the critics' point of view. You were also nominated for a BAFTA Award that same year.

SW: That's right. It was a very important film for me but probably less of a highlight than, say, Shakespeare in Love or Mrs. Brown. It was the type of film where songs had been already chosen before my arrival because they did play a role for the story, they marked the musical atmosphere of the film. This was very interesting for me as a composer since my responsibility was then shared, i.e. I was supposed to work on the dramatic side of the film in between the songs. There's still music that I wrote with some very nice piano stuff like in the delicate scenes where Billy is dancing alone in the streets, etc. SW: That's right. It was a very important film for me but probably less of a highlight than, say, Shakespeare in Love or Mrs. Brown. It was the type of film where songs had been already chosen before my arrival because they did play a role for the story, they marked the musical atmosphere of the film. This was very interesting for me as a composer since my responsibility was then shared, i.e. I was supposed to work on the dramatic side of the film in between the songs. There's still music that I wrote with some very nice piano stuff like in the delicate scenes where Billy is dancing alone in the streets, etc.

BS: Captain Corelli's Mandolin is a real pleasure, and -in our humble opinion- a masterpiece. Was it difficult for a British composer like you to write melodies with a strong Mediterranean feeling? BS: Captain Corelli's Mandolin is a real pleasure, and -in our humble opinion- a masterpiece. Was it difficult for a British composer like you to write melodies with a strong Mediterranean feeling?

SW: This was one of the happiest experiences in my life. Virtually everyone was very optimistic and we spent a lot of time recording the dances with musicians, all the mandolin music, etc.

A funny thing happened as regards the mandolin solos, indeed, because one day I went to John Madden's house and he said: 'Well, you know, I would like to listen to the mandolin themes but before you show them to me, I just have to go quickly buy a sandwich.'

I hadn't written those themes yet! So while he was out, I sort of figured out a theme that I could show and he liked it. Then I spent almost two weeks working on that particular music, trying to get a better theme, but finally we stuck to the one I had written originally!

BS: In Quills, wasn't it true that you specifically asked for some very rare instruments that were typical to the period of the picture (the 18th Century)?

SW: Well, I wanted to experiment with a different music. There was actually only one instrument from the period (the serpent) but I had like five or six other instruments that were specially made for the film.

BS: How did you come up with that?

SW: Philippe Kaufman, the director, wanted us to have a special type of music that when played in the presence of the Marquis de Sade didn't have the kind of perfect resonance of a more traditional instrument. He insisted on us achieving something that sounded brute and which had the kind of cruelty that somehow the character itself was demonstrating. Therefore we decided to develop a few percussion instruments plus a couple of strings and so we got it. SW: Philippe Kaufman, the director, wanted us to have a special type of music that when played in the presence of the Marquis de Sade didn't have the kind of perfect resonance of a more traditional instrument. He insisted on us achieving something that sounded brute and which had the kind of cruelty that somehow the character itself was demonstrating. Therefore we decided to develop a few percussion instruments plus a couple of strings and so we got it.

BS: Would you say that he is the kind of director who's really aware of the true role music can play in a film?

SW: Definitely! And he was a very inspiring director to work with as he provoked me to find the musical voice of the film. He insisted on having a score that was very individual and particular to that film, he didn't just want a dramatic or, say, mad film music but rather a unique style that could fit like a glove to his picture. To begin with it was quite a slow job but, in the end, it simply was a very rewarding experience for me. I wish I had again the opportunity to work with him again.

BS: Dreamkeeper is an ethnic-oriented work, with Native American instruments. Is it true that you performed a bass dulcimer, a bowed bow pit and a damnoni on your own?

SW: First the music editor and I went to North America and recorded some sessions with native musicians, so that was one element of it. And then we had some other native instruments being recorded and an orchestra as well. So, in the end, it was a mixture of some real native North American playing real ethnic instruments and, in addition to this, our modern interpretation of how this music could sound like from our perspective. In addition, I also had the opportunity to play a few of these instruments myself, like the ones you mentioned, given that I had later the chance to collaborate with another North American musician who flew to the UK for about three weeks. Yes, it was a very interesting project. SW: First the music editor and I went to North America and recorded some sessions with native musicians, so that was one element of it. And then we had some other native instruments being recorded and an orchestra as well. So, in the end, it was a mixture of some real native North American playing real ethnic instruments and, in addition to this, our modern interpretation of how this music could sound like from our perspective. In addition, I also had the opportunity to play a few of these instruments myself, like the ones you mentioned, given that I had later the chance to collaborate with another North American musician who flew to the UK for about three weeks. Yes, it was a very interesting project.

BS: Did you have to do much research?

SW: Yes. It was a big amount of work because of the size of the project. Since it's a TV production I had to write like two hours of music or so.

BS: Charlotte Gray marked another turning point in your career. Your music here is quite awe-inspiring. Was it Gilliam Armstrong's decision not to use the amazingly beautiful main theme except at the end of the film?

SW: I guess you're talking about that peaceful violin solo, which is used two or three times in the film, but I don't remember now at what particular part of it were those themes finally attached. I think the decision as to when and how to play it came as the result of the discussions we had about the score. SW: I guess you're talking about that peaceful violin solo, which is used two or three times in the film, but I don't remember now at what particular part of it were those themes finally attached. I think the decision as to when and how to play it came as the result of the discussions we had about the score.

BS: Gilliam Armstrong, the director, went on working with you for this picture after her previous experience with Thomas Newman in Oscar and Lucinda. Do you know how she came to choose you this time?

SW: I don't know. In fact, we had indeed a very funny relationship. This was the year 2001, right after the terrorist attacks in NY. She was based in Australia and she did not want to fly to the UK, plus there was also the fact that she had a young family. So in order to make this work, I kept sending her my music by post and then we would discuss it over the phone. In the end it turned out to be a good relationship but also a little tricky. I guess it would have been better, had we had the opportunity to see each other more frequently. I like to see people's faces!

BS: You first project in Spain was for the director Gerardo Vera, in Deseo (Desire), a somehow controversial film that takes place during the same period Charlotte Gray does, but which is drastically different. Your contribution shows a bold classicism, one that nonetheless still has the beauty of the so-called 'Warbeck trademark'. How was it like to work in this Spanish production, whose score was recorded in Prague if we are correctly informed?

SW: Well it was a very new experience in terms of how Gerardo Vera decided to approach me to give me some guidance. With other directors I usually have several meetings to discuss various things but here, he actually said he liked my music very much so, basically, he made with this flattering remark and then he simply asked me to write the music as I felt appropriate. SW: Well it was a very new experience in terms of how Gerardo Vera decided to approach me to give me some guidance. With other directors I usually have several meetings to discuss various things but here, he actually said he liked my music very much so, basically, he made with this flattering remark and then he simply asked me to write the music as I felt appropriate.

Later we had this one meeting in Madrid, I don't remember were it was, but there was a piano in the room and a few people from Lola Films around. I was supposed to play some of the tunes I had come up with and so I did. I remember very well that the only thing Gerardo said was: "Don't be afraid of going more emotional". And so I went.

I visited the Costa de la Muerte, where the picture was being shot, for a few days and it all was very inspiring so I'd say it was the startling beauty of that place and also the very subject of the story, this concept of a precipice that separates both lovers, the notion of an impossible union that helped me find the way with my music.

BS: How do you manage to write music for a film that is not being shot in your own language as it was the case here?

SW: Well, I did have the script in English, so I already knew the story. And then there's also the fact that I speak French, which is close to Spanish. So these two elements helped me, more o less, understand what was being said in Spanish. Probably I don't get 100% of the dialogues the first time I go through the picture, but when you've seen it a number of times you start understanding quite well what a character is saying.

In the end, you do work in pretty much the same way as you do in a film that has been shot in your own language, only here it takes a few more weeks to get to the same point. I do mean that you really do get to understand the musical rhythms of the speech, not just the overall concepts. Spanish is not a complete mystery to me. With other languages I would be blind, I think. Indeed, I did a Belgian film in Dutch and that was more difficult. But, again, when you know the script in advance, you also start to realize what they are saying onscreen as they are speaking.

BS: This last one picture is the Belgian-Danish co-production entitled Zaak Alzheimer, isn't it? BS: This last one picture is the Belgian-Danish co-production entitled Zaak Alzheimer, isn't it?

SW: That's right.

BS: Here you earned a nomination to the European Film Awards in 2004. Can you tell us something about this score which is virtually unknown in Spain?

SW: I think this is a really fantastic film! In Belgium they had a very big case a few years ago about paedophilia, where there were very high up people involved in sex with children and, if I'm not wrong, the whole issue is not yet over at the courts. This film is somehow involved in that world, but it's fiction. There's an assassin who's living in Marseille who suffers from Alzheimer and he does come to Belgium to kill some people. Once he's in Belgium, he discovers that the people he is supposed to kill are witnesses who could implicate these other people in committing these terrible things. So he turns against those who have hired him and he sets about destroying them. It's a kind of moral tale about a killer but within a real context, so it does really hit you hard as a subject. SW: I think this is a really fantastic film! In Belgium they had a very big case a few years ago about paedophilia, where there were very high up people involved in sex with children and, if I'm not wrong, the whole issue is not yet over at the courts. This film is somehow involved in that world, but it's fiction. There's an assassin who's living in Marseille who suffers from Alzheimer and he does come to Belgium to kill some people. Once he's in Belgium, he discovers that the people he is supposed to kill are witnesses who could implicate these other people in committing these terrible things. So he turns against those who have hired him and he sets about destroying them. It's a kind of moral tale about a killer but within a real context, so it does really hit you hard as a subject.

So, the music is heavily based on strings, an electric guitar and 3 percussionists who use filer cabinets to create the sounds. It was very interesting for me to write this score, because of the whole thing of having a main character that is getting in and out of this Alzheimer state where he does suddenly not know what he is doing and right then he just remembers it all. The music is sort of in and out of consciousness, not really mad but strange. I heard they are re-making the picture now in the United States.

BS: Did you notice many differences between working here at a Spanish production and somewhere else? What is it you liked the most?

SW: I don't' know. I guess I like it very much here because of how open Spanish people are. I've worked in Spain three times now and every time it's been very good. I do like Spanish music, composers, films, etc.

BS: And what do you like the least?

SW: It's hard to say. Like what?

BS: I don't know.

SW: Me either. I do enjoy it much working here, so I guess I expect to do it more often.

BS: Speaking of Spanish productions, you have just collaborated with a Spanish composer, Sergio Moure, in Cargo, a French-British-Spanish co-production which we learned about from Sergio during the I International Conference of Film Music - City of Úbeda. It must already be quite a challenge to be the only person in charge of the musical aspect of a film. Having to share this responsibility with other people must be even more difficult, isn't it? BS: Speaking of Spanish productions, you have just collaborated with a Spanish composer, Sergio Moure, in Cargo, a French-British-Spanish co-production which we learned about from Sergio during the I International Conference of Film Music - City of Úbeda. It must already be quite a challenge to be the only person in charge of the musical aspect of a film. Having to share this responsibility with other people must be even more difficult, isn't it?

SW: Working on this film wasn't easy. In principle, to have two composers with two different styles working together it's not possible, but in practise it sort of worked out pretty well. It's not the happiest process for any composer but, in the end, the result was good and we both can say we are glad with the outcome. We are even thinking of producing an orchestral suite which we hope to be able to record with the Galician Orchestra, the one we worked with for the film.

BS: In 2004 we received news that you had been chosen for Jean Jacques Annaud's latest film, Two Brothers, and once again Stephen Warbeck did not disappoint us, with a melodic and utterly emotive score. Was it you who convinced Jean Jacques to whistle the theme 'To Freedom'? BS: In 2004 we received news that you had been chosen for Jean Jacques Annaud's latest film, Two Brothers, and once again Stephen Warbeck did not disappoint us, with a melodic and utterly emotive score. Was it you who convinced Jean Jacques to whistle the theme 'To Freedom'?

SW: What happened was he played me a piece of music from another film and there was someone who whistled. He was at my house and he said he really liked to whistle and he also liked music in this style, so I wrote a tune with that in mind. Then, the recording was all wrong, we had someone professional doing it but the key was wrong and then we had to go back and get everything correct, what took some time. So, after this Jean Jacques decided to come back and do it himself.

BS: How was it like to collaborate with such a distinctive director as Jean Jaques Annaud? Do you know why he chooses to move from one composer to another so often (which, by the way, always provides excellent results)?

SW: I don't know. I don't even know if we will ever work together again. I think he likes to seat with the composer and work with him on the music. Perhaps some composers don't like it very much, they do prefer to say: 'These are my ideas and finished'. In addition he does a film every four years, so maybe he wants to do something else every time. Who was the composer involved in The Name of the Rose? SW: I don't know. I don't even know if we will ever work together again. I think he likes to seat with the composer and work with him on the music. Perhaps some composers don't like it very much, they do prefer to say: 'These are my ideas and finished'. In addition he does a film every four years, so maybe he wants to do something else every time. Who was the composer involved in The Name of the Rose?

BS: James Horner.

SW: Really? I like the film very much. I watched that film before I even started to write music for films in the early 80s. Do you know that they lost the script? Jean Jacques told me they had worked on the script for 8 months and then they were just about to meet the producer and show him the script when they simply pressed the wrong button in the computer and, that was it, all gone!

BS: Finally, let me ask you about your latest collaboration with John Madden for the film Proof, whose score we have recently reviewed. Being this a very different film and dissimilar also in a thematic sense to the ones that you and John have done before, how did you streamline your approach to this project?

SW: In the last two, three pictures we have done together we have used this technique of writing the music as we go along, instead of waiting and then recording it all at the end of the process. So we start first recording a little bit of music here, then we take a break and go for another piece of music and so on and so forth. This one took us three months. SW: In the last two, three pictures we have done together we have used this technique of writing the music as we go along, instead of waiting and then recording it all at the end of the process. So we start first recording a little bit of music here, then we take a break and go for another piece of music and so on and so forth. This one took us three months.

As to the style, well, it's not very much different from the kind of music I've written before, but it is indeed from what I've done for John Madden before. It's colder, I think.

BS: Exactly, it's less of a classical score, moving further away from the style you've grown us accustomed to and somewhat more in line with that of other composers, so to say, more popular nowadays, e.g. Thomas Newman or Alexander Desplat. Was this a conscious choice or rather one that happened because of the nature of the picture itself?

SW: It's hard to answer this question without actually having seen the film because it's the film that gives you the explanation to your question. This one is more contained and so it didn't ask for a chamber orchestra.

BS: Belgium, Denmark, Spain, the USA, the UK, etc. Is there no geographical boundary you want to set when approached to score a film?

SW: I don't want to set any boundaries here. Indeed John Madden is now working on something that hopefully we will be working in soon and which has something to do with this. There's even one song in Spanish that I'm working on, which is based on a poem called El Río Guadalquivir.

BS: Stephen, thank you very much for this very much interesting interview.

SW: You are welcome. It's been very nice talking to you, too.

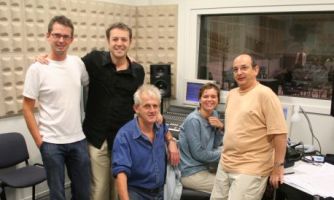

Interview performed by Sergio Gorjón

Questions by Asier G. Senarriaga, David Doncel and Eduardo González Joyanes

Transcript by Óscar Giménez and Sergio Gorjón

|